Utopia is a region in central Australia, around 250 kilometres northeast of Alice Springs, within an area generally known as the Sandover. The origin of the name Utopia is debated, some attributing the name to the original pastoralists and others have posited it as a corruption of Uturupa, which means ‘big sand hill’ – referring to a region in the northwest of the area.

Utopia extends over some 3,500 square kilometres. The desert landscape of Utopia changes with the seasons and features grassy plains and rocky outcrops along the main waterway, the Sandover River, which is usually a dried sandy expanse, dotted with trees. The summer is hot and dry, yet in winter, the temperature can drop to below zero degrees Celsius at night. The features and colours of the region are reflected in the art: the fine dots of grass seeds and bush fruit; the azure expanse of sky; the bright orange-red sand; the soft yellow-green grass; the white ghost gum trees; the white dotted flowers of the bush plum; the tracks in the sand of bush turkeys and mountain devil lizard; the rainbow colours of spring flowers.

Image: Sandover River, Central Australia

Language and Clans

The people of Utopia reside in small communities of between twenty to one hundred people, where they can be close to their custodial country and live a relatively traditional lifestyle, including hunting and gathering food. The sixteen homelands include: Anelthyey (Boundary Bore;) Iylenty (Mosquito Bore); Arawerr (Soapy Bore); Ngkwelay (Kurrajong Bore); Aharlper Store; Ankerrapw (Utopia homestead); Artekerr (Three Bores); Akay Soakage (Mulga Bore); Antarrengeny and Ngkwarlerlanem.

The two languages that predominate today are the Alyawarr and Anmatyerr language groups. Important ancestors of the area include the mountain devil lizard (arnkerrth), the emu (arnkerr) and kangaroo (aherr).

Image: Sandover Highway, road to Utopia, Central Australia

History

European occupation of the Sandover region began in the early 1880s in the southern Davenport Ranges, on the Elkedra and the Bundey rivers. These settlements were not well resourced and were short of surface water. By 1895, most of these settlements were abandoned as a result of drought and conflict with the Aboriginal inhabitants. In 1928, two portions of land – which later became Utopia station – were leased by cattlemen. The remoteness of central Australia resulted in comparatively slow intervention by Europeans compared to the fertile coastline, which enabled traditional Aboriginal culture to remain strong. Many Aboriginal people worked on the homesteads of Alcoota, Woodgreen, Utopia and MacDonald Downs. The men were employed as stockmen and the women in domestic labour. Many were given anglicised names, such as Bird, Kunoth and Holmes, which still carry on to today.

Utopia is believed to have been optimistically named by the German brothers Trot and Sonny Kunoth, who took out the pastoral lease in the 1930s.1 In 1965, the Chalmers family, who had owned the neighbouring property MacDonald Downs since 1923, acquired the lease.2 In 1979, it was handed back to the Anmatyerr and Alyawarr people as Aboriginal freehold land, following the sale of the Utopia lease by the Chalmers to the Aboriginal Land Fund Commission.

Today, the population of the general area of Utopia is around 1,000 people. There is a central store at Aharlper (also spelt Arlparra), a school and a health centre. The area is administered by the Urapuntja Council Aboriginal Corporation, through the Barkly Shire Council.

Art and the Art Centre

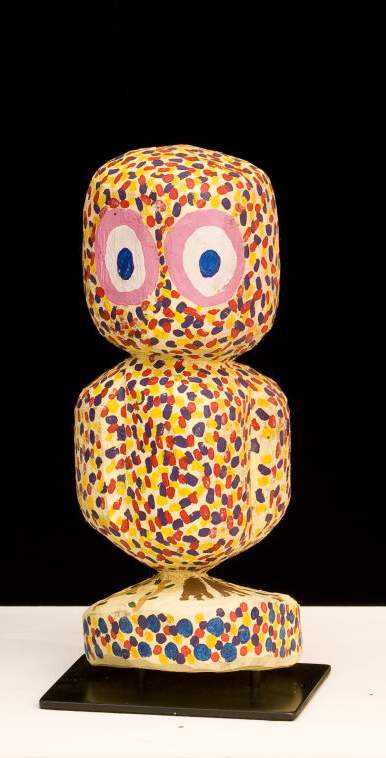

Art has always been significant in Utopia with body painting and sand paintings being important aspects of ceremony. There is also a tradition of woodcarving which continues today, as seen in the painted and carved works by Josie Kuoth Petyarr, Dinni Kunoth Kemarr and the owls (Arrkerr) of Trudy Raggett Kemarr.

The batik art medium was introduced to Utopia in 1977, by Susie Bryce and Yipati Williams (a Pitjantjatjara woman), in craft classes that also included sewing, woodblock printing and tie-dyeing. Batik was the most popular and the following years saw a number of Utopian women gain national and international acclaim with their batik creations. Their expertise was further developed by Jenny Green and Julia Murray.

Image: TRUDY RAGGETT KEMARR 1980-, Arrkerr, 2007, synthetic polymer on carved wood, © the artist.

In 1987, Rodney Gooch from the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) took over the operations of the Utopia Batik Group and encouraged the women to create their story and depict their country on batik. This collective community batik project culminated in the exhibition Utopia: A Picture Story with 88 artists contributing (all women, except Lindsay Bird Mpetyan and nearly all either Anmatyerr or Alyawarr speakers). This collection of batiks was shown in Adelaide, Sydney, Perth and Melbourne before travelling to Ireland, Germany, Paris and Bangkok.

The late 1980s saw a shift from textile to canvas as a way to translate the motifs of their Dreaming stories. The mostly women artists often depicted ceremonial body paint designs (Awelye) with its direct association with the act of painting. A Summer Project: The First Works on Canvas was shown at the SH Ervin Gallery in Sydney in 1988-89.

Perhaps the most notable characteristic of the artists of the Sandover area is their ability to experiment and diversify their artistic output. From the origins of batik and the expansive imagery, to painting on canvas, the artists worked with wood making painted sculptures of animals and people, to printmaking and the production of the collection of 72 woodblocks known as The Utopia Suite, while others created landscapes on the remnants of wrecked cars.

Images: POLY NGAL 1936 -, Bush Plum country, 2002, synthetic polymer on linen © the artist (left) and Poly Ngal, November 2005 (right)

The paintings of Alyawarr and Anmatyerr speaking Aboriginal artists are contemporary dialogues or translations of the oldest laws and culture. Although the paintings are individual in creation, the stories and the countries depicted are shared by many. Their paintings have arisen through the stories of their cultural heritage and depictions of the food and flora of their landscape. Stylistically, the painting of Utopia largely can be considered in two categories, that of gestural abstractionism, such as the work of Emily Kam Kngwarray and the fine stippling techniques as seen in the work of the Ngal sisters and Kathleen Petyarre.

Perhaps no other group of artists from Central Australia has explored the myriad possibilities of the ‘dot’ as widely as those from the Sandover, and almost all artists have used this technique at some time or another.3

The Utopia Cultural Centre and Utopia Awely Batik Corporation was funded between 1995 and 1998 by ATSIC. Then Urapuntja Artists Utopia, established as a community artists’ organisation funded through ATSIC and affiliated with Desart, ran until 2002. There were some 150 artists, both men and women, working through the centre. The artists experimented with different mediums. In 2004, the Utopia artists joined with Artists of Ampilatwatja, further to the north, to form Sandover Art. A commercial outlet was established in Alice Springs, however, the new organisation ceased shortly thereafter.

The dedication and enthusiasm of firstly Rodney Gooch, and subsequently, Simon Turner, was essential to the running of the art centre. There is currently no Aboriginal run art centre within Utopia. Some artists have a working relationship with the Holt family at Delmore Downs and others work directly with dealers and galleries, including Lauraine Diggins Fine Art.

A series of population health surveys (1986–2004) have shown that Utopia people are significantly healthier than comparable groups in other regions of Australia – something that has been attributed to the ‘outstation way of life’. The people harvest and consume traditional foods – and to some extent medicines – especially the elders.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

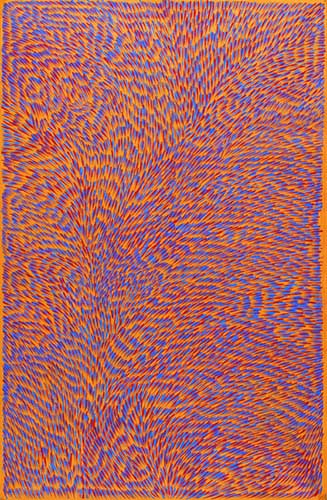

The most celebrated artist to emerge from Utopia is Emily Kam Kngwarray, whose work continues to be exhibited at an international level. Emily grew up in the bush, and performed domestic work at station homesteads during her adolescence. She first took up batik as an artistic medium in her senior years and then started painting in 1988, and in 1990 had her first solo exhibition in Sydney.

Image: EMILY KAM KNGWARRAY c.1910 -1996, The Artist’s Country, 1991, synthetic polymer on canvas © the artist’s estate

As a leading example of contemporary Australian art, she was represented at the Venice Biennale in 1997, the year after her death. In 2008 a retrospective exhibition was held in Japan and it was the most comprehensive exhibition by any Australian artist curated for an overseas venue.

Emily proved an important model and teacher for many of the artists still working at Utopia today. Her painting reflects the fluidity and confident marks that continue to characterise the work of artists from the Utopia region. The influence of Emily Kam Kngwarray in modern painting is yet to be fully realised, let alone appreciated.

The Petyarr Family

Other well known Utopia artists include the famed Petyarr sisters; there are seven sisters – including Kathleen, Gloria and the late Nancy Petyarr – who have received international recognition for their delicate and beautifully formed portrayals of their country and culture.

Images: Gloria Petyarr, wearing Hermes silk scarf with her design (left) and GLORIA TAMERRE PETYARR c.1945 -, Leaves, 2002, synthetic polymer on linen, © the artist

In 2008, Gloria Petyarr became the first Australian artist to be commissioned by the international fashion house, Hermes, to create a design for their famous silk art scarves. This commission came about as a result of Lauraine Diggins Fine Art exhibiting Gloria’s work at ArtParis 2006, where she caught the eye of the artistic director of Hermes, Pierre Alexis Dumas. Gloria is one of Utopia’s most exhibited, travelled and diverse living Indigenous artist and is regarded as being an integral part of the history of painting in Utopia; an artist whose originality and diversity exemplifies the evolution, particularly of women’s art. She was awarded the prestigious Wynne Prize for Landscape Painting by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1999.

Gloria’s sister, Kathleen, won the coveted Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 1996 and was the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, in 2001. She is recognised as one of the premier contemporary painters of the central and western desert art movement. Kathleen’s work is executed in the finest detail and depicts the travels of Arnkerrth, the Mountain Devil Lizard. Her compositions draw on diagonal tensions, illustrating travels, lakes and sacred sites. Kathleen’s abilities as a painter are matched by her seniority in cultural knowledge and matriarchal duties of custodianship.

Nancy also painted the Mountain Devil Dreaming, depicting the journey of the little lizard along the dreamline. The lizard changes colour as it travels from dawn to dusk and this helps it to travel undetected. Nancy’s paintings were also based on women’s ceremonial body paint designs, Awelye; the translation to canvas offering a further aesthetic appreciation of an art tradition grown from one of the world’s oldest living cultures. Nancy maintained a centred and involved family life style at Utopia, with family members who were also artists.

This included daughter Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray, grand-daughter Genevieve Loy Kemarr and son-in-law Cowboy Loy Pwerl, who are all proving to be leading artists today. Elizabeth is a two-time finalist in the Wynne Prize for landscape painting at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Cowboy has been a finalist in The Blake Prize for Religious painting, while Genevieve has been a finalist in a number of art awards including the Churchie for emerging artists and the Paddington Art Award.

Images: Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray at Wynne Prize AGNSW, 2010 (left) and ELIZABETH KUNOTH KNGWARRAY 1961-, Gathering Seeds in My Grandmother’s Country, 2012, synthetic polymer on linen © the artist

The Ngal Sisters

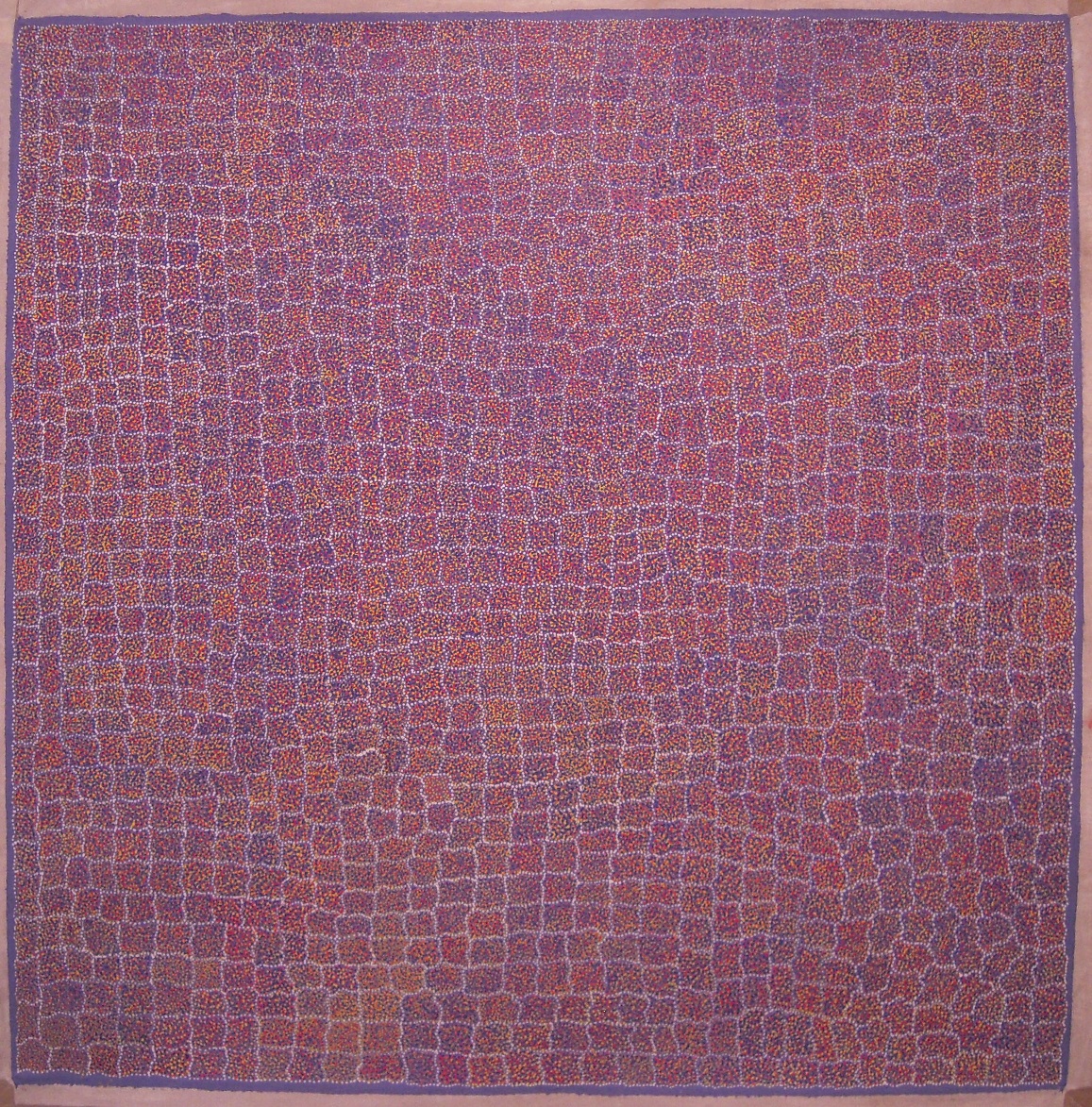

Another significant family group are the Ngal sisters; Poly, Kathleen and Angelina, who reside at Camel Camp, close to the Sandover River. Each sister has been a finalist in the Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award and both Kathleen and Angelina were finalists in the Wynne Prize for Landscape painting at the Art Gallery of NSW. Largely, the subject of their painting is the Bush Plum (Arnwekety); these are journeys mapping the bush plum country and associated women’s ceremonies, which is represented through a focus of many coloured dots flooding the canvas. Other subjects include the many coloured wildflowers of their country, producing patchworks of colour that hint to the viewer of an ethereal landscape.

Image: Angelina Ngal, November 2005 (left) and ANGELINA NGAL c.1947-, Women’s Dreaming – Mother’s Country, 2005, synthetic polymer on linen © the artist (right)

The Morton Sisters

Another family group are the Morton sisters, Ruby, Lucky, Sarah and Hazel, who all reside at Rocket Range or Inkawanyere, called Rainbow Country by these artists.

Artists: Past and present

| Dinni Kunoth Kemarr | Trudy Raggett Kemarr | |

| Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray | Hazel Morton Kngwarray | |

| Ruby Morton Kngwarray | Sarah Morton Kngwarray | |

| Gladdy Kemarr | Genevieve Kemarr Loy | |

| Angelina Ngal | Kathleen Ngal | |

| Ada Bird Petyarr | Josie Kunoth Petyarr | |

| Violet Petyarr | Nancy Kunoth Petyarr | |

| Greenie Purvis Petyarr | Cowboy Loy Pwerl | |

| Barbara Weir | Poly Ngal | |

| Emily Kam Kngwarray | Kathleen Petyarre | |

| Lucky Morton Kngwarray | Gloria Tamerr Petyarr | |

| Lily Sandover Kngwarray | Minnie Pwerl | |

| Lindsay Bird Mpetyane |

Further References

A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, Malakoff Fine Art Press, 1989, p.121Boulter, Michael, The Art of Utopia, a New Direction in Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Craftsman House, 1991Caruana, Wally, Aboriginal Art, Thames & Hudson, London, 2003, pp.145 -153

Earth’s Creation – The paintings of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Malakoff Fine Art Press, 1998

Isaacs, Jennifer, Spirit Country: Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art, Hardie Grant Books, 1999, pp.29 – 30

Isaacs, J et al, Emily Kngwarrey Paintings, Craftsman House, 1998

Kleinert, Sylvia & Neale, Margo (general eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp.218, 725

Murray, Julia, ‘Drawn Together: the Utopia batik phenomenon’ in Ryan, Judith [et al.], Across The Desert: Aboriginal Batik from Central Australia, National Gallery of Victoria, 2008, pp.116 – 121

Neale, Margo, Emily Kame Kngwarrey, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998

Neale, Margo, Utopia: the Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, National Museum of Australia Press, 2008

Nicholls, Christine, Art Without Borders, An Individual Perspective: From The Indigenous Collection of Lauraine Diggins, Deakin University, Melbourne, 2009, p. 5

Nicholls, Christine & North, Ian, Kathleen Petyarre: Genius of Place, Wakefield Press, 2001

Rowley, Kevin et al. Urapuntja Health Service and Utopia Community: A Report to the Teasdale-Corti Comprehensive Primary Health Care Project, ‘Revitalising Health for All’, Urapuntja Health Service Aboriginal Corporation, June 2011, p. 7

Perkins, Hetti ed. One Sun One Moon: Aboriginal Art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2007

Utopia A Picture Story 88 Silk Batiks from the Robert Holmes a Court Collection, Heytesbury Holdings, 1990

Utopia: Ancient Cultures New Forms, Heytesbury, 1998

Utopia Today, Malakoff Fine Art Press, Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne, 2009

Remote area health corps Urapuntja health Services, Australian Government Report, 2009

Foot Notes

1. Rowley, Kevin et al. Urapuntja Health Service and Utopia Community: A Report to the Teasdale-Corti Comprehensive Primary Health Care Project, ‘Revitalising Health for All’, Urapuntja Health Service Aboriginal Corporation, June 2011, p. 7. ↩

2. Ibid, p. 4. ↩

3. Green, Jenny, Holding the Country: Art from Utopia and the Sandover, in One Sun One Moon: Aboriginal Art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000, p.206. ↩