The art centre at Yirrkala, Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, derives its name from its immediate location. It is a generic term for the region of North East Arnhem Land and named as such by all dialects of the region, that is, Yolngu Matha – the language of the people. Buku-Larrnggay translates as the ‘feeling on your face as the first rays of the sun touch it’, referring to Buku-Larrnggay as the most easterly aspect in the Top End, a region known also as Miwatj. Miwatj translates as sunrise country, while Mulka is a sacred but public ceremony, which also means to hold or protect.

Image: Sunset at Bremer Island, off the North East coast of Arnhem Land

Yirrkala is situated in Eastern Arnhem Land, some 700kms east of Darwin, near Nhulunbuy on the Gove Peninsula. Subject to a monsoonal climate, the land is almost untouched by Western development, beside a couple of glaring exceptions: a bauxite mine and an alumina refinery. Gove Peninsula is an area of spectacular natural beauty, with vast tracts of unspoiled land, beaches and ocean.

The land is characterised by a mixture of savannah woodland, wetlands, rich in birdlife and patches of forest and rocky escarpment. The oceans are teaming with fish, stingrays, and shark. The sea is also home to Bäru, the ancestral crocodile. During the Wet Season, from December to May, the roads become impassable and all access to the region is by air or sea.

Language and Clans

The country has been inhabited for at least 50,000 years by Aboriginal people whose culture is based on a strong sense of connection to land and sea. Records indicate that the Macassan fishermen from East Indonesia, with whom the Yolngu established close ties, were amongst the first visitors to Australian shores. It would appear that there were trades in which the Yolngu received knives, cloth and tobacco. Many Yolngu words, songs and dances encompass influences from these Macassan traders.

The major clans of the Miwatj region are; Gumatj, Rirratjingu, Djapu, Manggalili, Marrakulu, Madarrpa, Galpu, Dhalwangu, Dätiwuy, Ngaymil, Djarrwark, Munyuku, Djambarrpuyngu, Wangurri, and Dhudi-Djapu. Yirrkala is ancestral land belonging to the Rirratjingu clan.

History

Yirrkala was founded as a Methodist Mission in 1935, following the invitation of elder Mawalan Marika, to the missionary Wilbur Chaseling. The mission supported the creation of artworks and these were amongst the earliest commercial Aboriginal art marketed by Methodist Overseas Mission. It is arguable that the art emerging from Yirrkala in the mid 1950s was a catalyst in the non-Aboriginal art world’s appreciation of Indigenous art, as a unique and profound independent art tradition.

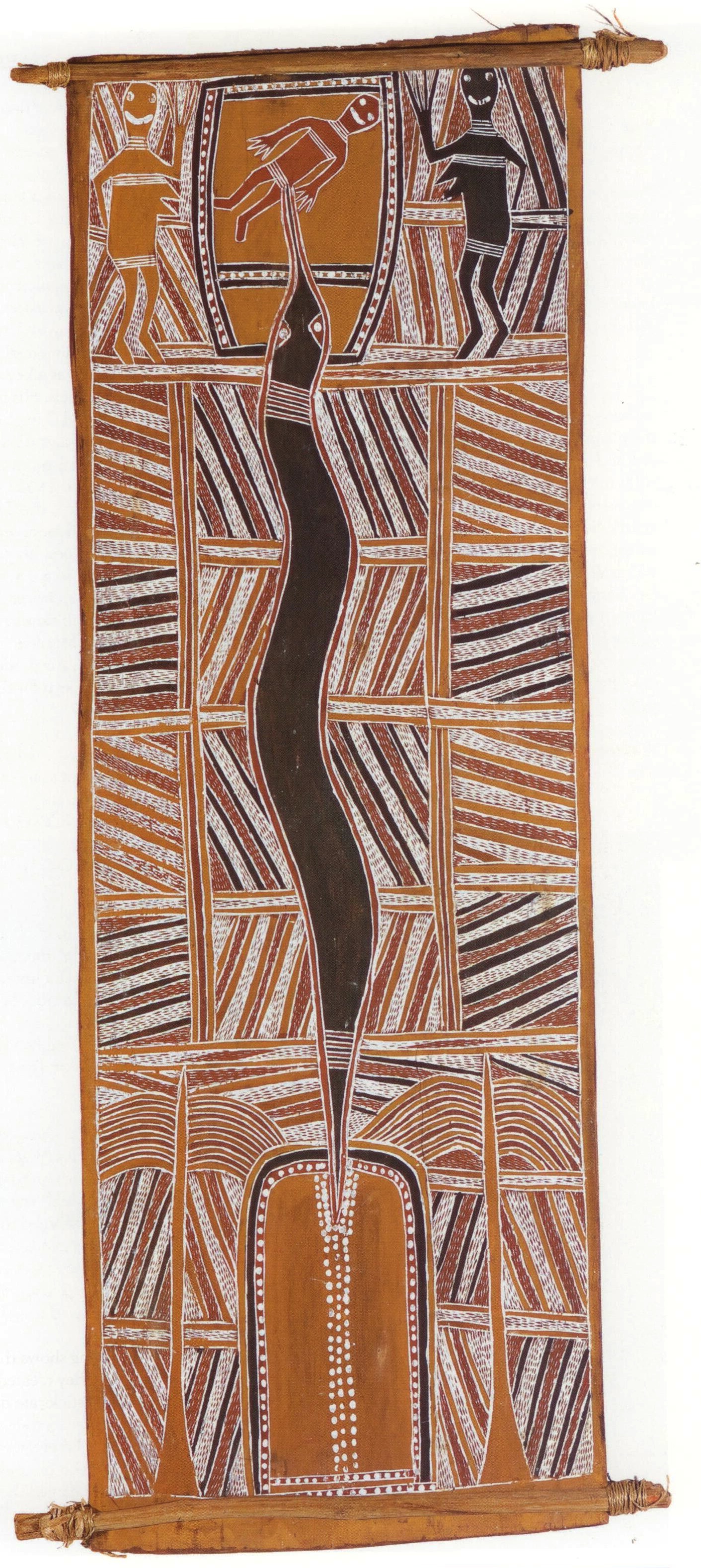

Image: MITHINARI GURRUWIWI c.1929-1976, Garrimala Lagoon, c.1965, natural pigments on bark, © the artist, courtesy Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

The artists of Yirrkala were amongst the first Indigenous Australians to recognise the power of visual art as a political tool. Firstly, there were the famous Yirrkala Church Panels, which depict each of the Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties and were located strategically on either side of the cross in the Mission church. They were statements that there was no difference in the validity of the beliefs, of both Christian and Aboriginal people.

The Church Panels were produced in 1962, at the suggestion of Narritjin Maymuru. The panels were collaborative works and represented the paintings of the clans of the Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties. The Panels grew out of the syncretic relationship that had developed between the Yolngu religious leaders and Methodist missionaries, and explain the relationship the Yolngu have with their land.

Dhuwa moiety panel depicts the Djang’kawu ancestral beings at Burralku (the island of the dead) with the morning star overhead; their journey inland from the landing point of the Djang’kawu at Yalangbara, and the creation of water holes and the disseminating of the Laws; saltwater and freshwater sites in various clan countries; and the Shark ancestor Mäna.

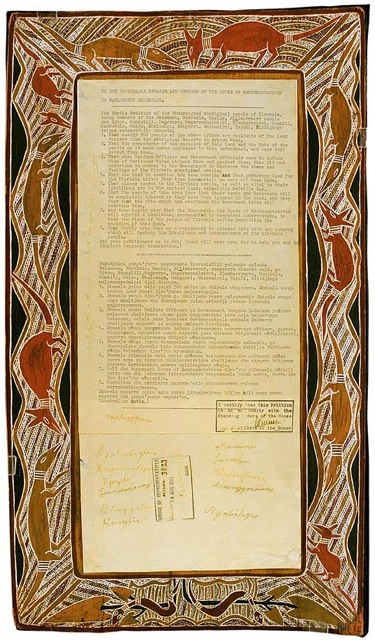

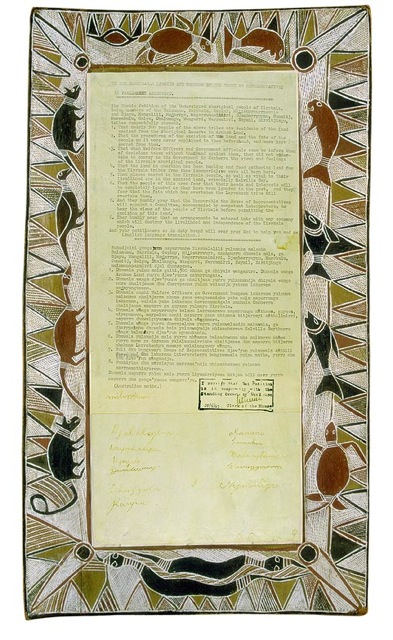

Image: The Yirrkala bark petitions 1963 (Dhuwa and Yirritja panels) described Yolngu law and the traditional relationship to land in both English and the Gumatj language. These petitions from the Yolngu people of Yirrkala were the first traditional documents recognised by the Commonwealth Parliament of Australia © the artists, courtesy of the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre.

Yirritja moiety panel shows the meeting of the Yirritja ancestor beings Barama, Gulparemun and Lany’tjung, and the giving of the Law to the Yirritja clans; the Gumatj clan ancestors Wirrili and Murrirri, and the Gumatj inland stony country and saltwater country; the Manggalili clan country at Djarrakpi with the ancestral guwak (koel cuckoo) in his human form; and the ancestral woman Nyapililngu, above the saltwater and cloud designs that link the various saltwater Yirritja clans to each other. At the top of the panel the guwak and marrngu (possum) ancestors link the Yirrtja clans of the island. The Yirrkala Church Panels are currently on display in the museum at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka.

Following the Church Panels was the historic Bark Petition of 1963, now on display at Parliament House, Canberra. The Bark Petition (completed by various Yirrkala artists, including: Watjung Marika, Yama Marika, Munggarawuy Yunupingu Narritjin Maymuru, Wandjuk Marika, Mawalan Marika, Jurriny, and Munggarawuy Yunupingu) was produced when the Yolngu became aware of the threat to their land posed by mineral exploration. Upon the discovery of bauxite in the area, the Australian Government proposed to excise a portion of land from the Aboriginal reserve and to lease it to a French mining company. Following a visit by two parliamentarians (Kim Beazley Sr. and Gordon Bryant) to Yirrkala, the community sent a petition to the Parliament in Canberra. The petition was a plea for the recognition of their title to the land, and was presented as two bark paintings, one Yirritja and one Dhuwa. The letter was reproduced in English and Rirratjingu, the language of the landowners of Yirrkala. The letters were affixed to sheets of stringybark, and the borders were painted with sacred designs by members of the clans, whose lands were threatened by the mining venture.

Ultimately the Bark Petition was unsuccessful in stopping the mining, however, it has played a vital part in subsequent actions in which the Yolngu people struggled for land rights and sovereignty. In 1976, they were finally granted land rights with the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act.

The Yolngu continued assert their connection to land with their art future legal cases, including: the Gove Land Rights Case, the Woodward Royal Commission, the Barunga Statement, the Yirrkala Homeland Movement, the Land Rights Act (NT) 1976, the Both Ways Education Bilingual Curriculum, and through the world renowned contemporary music band Yothu Yindi. In recent years the Garma Festival and Wukidi Larrakitj installations have used miny’tji to continue to rebut the myth of ‘Terra Nullius’1. The latest chapter in this history is the success of the Saltwater Collection of Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country.

Image: Exhibition catalogue cover: Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country, Buku Larrnggay Mulka, 1999

Art and the Art Centre

Commercial trade in the Top End during the 1960s saw collectors acquiring barks, many of which ended up in public museums and galleries. One of the precursors was Narritjin Maymuru, who sold his own artwork from a beachfront gallery he established and he is counted among the art centre’s main inspirations and founders. Following self-determination for Arnhem Land in 1975, the artists established the community controlled art centre, with a view to further their economic independence, cultural security over sacred designs, and to maintain political and intellectual sovereignty. Initially it was set up in the old ‘hospital’ or clinic. Additions to the original building have included a museum, with an annex for the seminal Yirrkala Church Panels, the jewels of the collection; a screen printing workshop; extra gallery spaces; a theatrette and multi-media centre; and a dedicated limited edition print workshop staffed by Indigenous artists. A feature of the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Museum is the collection of works specifically commissioned by elders in the mid-1970s and early 1980s, to show the ancestral connection of Yolngu clans to their country.

Buku-Larrnggay Mulka’s artists are located in Yirrkala and in the approximately 25 homeland centres within a radius of 200 kilometres. The sacred art of this region details the spiritual forces behind the ongoing creation, and continuing identity of the fresh and saltwater country of the Miwatj region. The coastline and hinterland are largely unspoiled and still managed by the traditional owners. The ecosystems of both the land and sea are pristine and provide abundant food, subject to the season, including yams, fruits, fish, kangaroo, wallaby, turtles and their eggs, dugong, emu, crayfish, oysters, mussels, tortoise, stingray, honey and more. These foods, and the land that supports them, are a seamless part of the holistic Creation, celebrated and maintained by almost continuous ceremonial activity. There is a constant interplay between the Law, the Land, the art of the Yolngu, their ceremony and lifestyle.

Under Yolngu Law the ‘Land’ extends to include the sea. Both land and sea are connected in a single cycle of life, for which the Yolngu hold the songs and designs. To demonstrate their rights and responsibilities over specific areas of both coast and sea, and to protect those same marine environments from abuse by outsiders, the landowners unified to make the Saltwater Collection of Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country in 1997. The collection of 80 bark paintings made by 47 Yolngu artists, is featured in a publication of the same name. After a national tour from 1998-2001, the Saltwater Collection is now held at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney and formed part of the Yolngu legal case for recognition of these rights.

In 2008 a precedent was set when the High Court recognised Yolngu ownership of the inter-tidal zone in Gawirrin Gumana V the Northern Territory Government, known as the Blue Mud Bay case. This resolved the decade long struggle started by the Saltwater Collection.

Despite developments in art practice, the elders have resisted a shift to painting the sacred title deeds of their country on canvas or board using synthetic polymer paint, opting instead to continue the use of nuwayak, or sheets of bark.

The age-old miny’tji, or sacred designs, belonging to each particular artist and their clan are produced using a meticulous layering of individual strokes to produce a cross hatched pattern readable by those with knowledge, as belonging to a particular estate, clan, state of water, moiety and place.

Significant Creation Stories

The Djang’kawu Sisters of the Dhuwa moiety

Inarguably, the most important story of the Yolngu people of the Dhuwa moiety, is that of the creative journey of the Djang’kawu sisters, which links the countries belonging to the string of Dhuwa moiety clans. Although there are a number of variations in certain details from clan to clan, the basic story is consistently agreed upon by all participating clans.

Image: WANDJUK MARIKA c.1930-1987, Wagilag Python emerging from the waterhole at Mirarrmina 1966-67, natural pigments on bark, © the artist’s estate Courtesy Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

According to the Rirratjingu clan account, the Djang’kawu brother and his sisters, Bitjiwurrurru and Madalatj, came to Eastern Arnhem Land from Burralku (a mythical island to the east), long ago. Travelling in their canoe, the Djang’kawu followed Banumbirr, the morning star, to land at Yalangbara, bringing with them the first dawn and the light and warmth of day. It was a joyous journey, as they experienced the sounds and expressions of the natural world, and came across various sea creatures, birds and flora, singing and naming them as the sisters recognised them. Their brother, who lacked their knowledge of the cosmos, accompanied them and appeared to be known only as Djang’kawu. They arrived at Yalangbara and celebrated the creation of the environment. As the site of both the end of their epic sea journey, and the beginning of their inland travels, the great sand dunes at Yalangbara are one of the most dramatic features of Arnhem Land. It was at Yalangbara that the Djang’kawu gave birth to the first human member of the Dhuwa moiety and accordingly, it is sacred and held with the utmost religious respect for all Yolngu people, including the Yirritja moiety members as their mothers remain as Dhuwa.

From Yalangbara they journeyed west, following the course of the sun, from sunrise to sunset. Each sister carried a twined conical basket filled with sacred objects (rangga) and a pair of digging sticks (ganinyidi) or walking sticks (mawalan), which they used to gather food and to pierce the ground to create wells and fresh water springs. Decorating the arms and basket of the Sisters were many tasselled cords made from the orange breast feathers of the red-collared lorikeet.

As they travelled, the Djang’kawu continued to see and named the places, plants, birds, fish and other animals. They also met other Wangarr2. In each of the various Dhuwa clan countries, they gave birth to the first people of the clan, named them and gave them language, sacred objects, songs, signs and ceremonies. They placed these sacred objects in waterholes, and created trees and other things by planting them in the ground.

On the way the Djang’kawu lost their basket of sacred objects. There are differences in this part of the story from clan to clan as to exactly how and where the loss occurred. One story suggests that the Sisters hung the basket up in a tree when they went to gather shellfish and men stole them; another story says that the men burned the bushes where the basket was hidden so that the Djang’kawu would believe they had been destroyed. In any event, the loss of the basket meant that the control of religious law passed to men.

Another point of contention in this story is the number and identity of the Djang’kawu. According to the Rirratjingu, Galpu and other clans in the east of the region, two sisters and a brother travelled together, although the brother is less frequently acknowledged especially by the women. However, in the version of the Liyagalawumirr, and other clans to the west, no brother is mentioned.

Eventually the Djang’kawu left the Yolngu country by following the setting sun into the west. The central themes of the Djang’kawu mythology are of creation and fertility, the source of sacred objects, and the Sisters’ loss of their baskets, and hence the transfer of esoteric knowledge from women to men.

Although a number of artists paint aspects of the Djang’kawu story, the most celebrated works are those of Mawalan, Mathaman and Wandjuk Marika. Spectacular examples were collected by Dr Stuart Scougall and gifted to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Today the tradition continues with other Rirratjingu artists such as Banduk, Dhuwarrwarr and Wanyubi Marika.

For the Yirritja moiety: Crocodile Ancestor

Ancestor spirit Bäru is a primal force taking the form of both a human and a crocodile. The Madarrpa clan, who live on the shores of Blue Mud Bay, are his direct descendants.

Bäru the crocodile man came originally from Mararlba country, where he married a blue-tongued woman. One day his wife was cooking shellfish (maypal) in the fire. Bäru demanded that she give them to him but she refused. During the ensuing quarrel Bäru pushed his wife into the fire and her arms and legs were badly burned. She turned herself into a blue-tongued lizard and ran and hid in a hole. Her clan, enraged at the Bäru, threw burning coals on his back, which burned him in the diamond pattern now associated with the crocodile. In his pain, Bäru jumped into the water and changed himself into a crocodile. Another version is that his bark shelter caught on fire and the burning bark sheets collapsed on his back.

After this event, Bäru left Mararlba and made his Dreaming place in Buigala Creek. Bäru’s spiritual country is the estuarine mangrove jungles on the northeast Arnhem Land coast, where crocodiles build their nests today. This area where saltwater and freshwater countries meet is symbolic of fertility.

Bäru is also associated with fire. Yirritja fire designs are compositions of diamonds, which are symbolic of the cracked pattern burned into crocodile skin in the creation era. The interaction of dangerous creatures like crocodiles and stingrays, each of which can inflict pain, is also a metaphor for the pain involved in initiation and ‘men’s business’.

Artists: Past and present

| Bunbatjiwuy Dhamarrandji | Gungguyama Dhamarrandji | |

| Gunybi Ganambarr | Larrtjannga Ganambarr | |

| Mowarra Ganambarr | Birrikitji Gumana | |

| Gawirrin Gumana | Mithinari Gurruwiwi | |

| Djalu Gurruwiwi | Djambawa Marawili | |

| Bakulanay Marawili | Marrirra Marawili | |

| Nuwandjali Marawili | Banduk Marika | |

| Langani Marika | Mathaman Marika | |

| Mawalan Marika | Wandjuk Marika | |

| Wanyubi Marika | Baluka Maymuru | |

| Galuma Maymuru | Naminau Maymura-White | |

| Nänyin Maymuru | Narrtjin Maymuru | |

| Wätjung Mununggiritj | Mutitjpuy Mununggurr | |

| Dula Ngurruwuthun | Munuparriwuy Wanambi | |

| Marrnyula Munungurr | Djutjadjutja Munungurr | |

| Yananymul Munungurr | Bowathay Munyarryun | |

| Dundiwuy Wanambi | Djawuyma Wanambi | |

| Guwayguway Wanambi | Mithili Wanambi | |

| Wolpa Wanambi | Wukun Wanambi | |

| Dhukal Wirrpanda | Djirrirra Wunungmurra | |

| Djarrayan Wununmurra | Yangarriny Wununmurra | |

| Nawurapu Wununmurra | Barrupu Yunupingu | |

| Deturru Yunupingu | Djarrkutjarrku Yunupingu | |

| Gaymala Yunupingu | Gulumbu Yunupingu | |

| Miniyawany Yunupingu | Munggurrawuy Yunupingu | |

| Nyapanyapa Yunupingu |

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Howard Morphy, Margie West and Buku-Larrngay Mulka Art Centre, and in particular Andrew Blake and Will Stubbs in the compilation of this document.

Further References

Arnhem Land Bark Paintings From Yirrkala and Milingimbi c.1965: The Anita Castan Collection, Benalla Art Gallery, 2002

Buwayak-Invisibility, Annandale Galleries, March 2003

Caruana, Wally, ‘Waglak and Djang’kawu: Ancestral paintings in the public domain’, in Art From Land: dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal Art, Morphy, Howard and Smith Boles, Margo (ed.), University of Virginia, 1999

Caruana, Wally and Lendon, Nigel, The Painters Of The Wagilag Sisters Story 1937-1997, National Gallery of Australia, 1997

Diggins, Lauraine, (ed), A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, Malakoff Fine Art Press, 1989, pp.24-25

Groger-Wurm Helen, Australian Aboriginal Bark Paintings and their Mythological Interpretations, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1973

Hutcherson Gillian, Djalkiri Wanga: The land is my Foundation: 50 years of Aboriginal Art from Yirrkala, Northeast Arnhem Land, The University of W.A. Berndt Museum of Anthropology, 1995

Hutcherson Gillian, Gong-Wapitja, Women and Art from Yirrkala, Aboriginal Studies Press, 1998

Laverty, Colin, Beyond Sacred: Recent Paintings from Australia’s Aboriginal communities. The Collection of Colin and Elizabeth Laverty, Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2008

MacKnight, Campbell, The Voyage to Marege: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia, Melbourne University Press, 1976

Mountford, Charles, Records of the American-Australian expedition to Arnhem Land, vol. 1 Art, Myth and Symbolism, Melbourne University Press, 1954

Morphy, Howard, ‘ Religion and Society in Eastern Arnhem Land’, in Art From The Land: dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal art, Morphy, Howard and Smith Boles, Margo (ed.), University of Virginia, 1999

Morphy, Howard, Journey to the Crocodiles Nest, Institute of Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1984

Morphy, Howard, Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System of Knowledge, University of Chicago Press, 1991

Morphy, Howard, Aboriginal Art, London: Phaidon Press, 1998

Nicholls, Christine, An Individual Perspective: From the Indigenous Collection of Lauraine Diggins, Deakin University, 2009

Rirratjingu Ethnobotany: Aboriginal Plant use from Yirrkala Arnhem Land, Australia Parks and Wildlife Commission, N.T., 1995

Ryan, Judith, Spirit in Land, Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land, National Gallery of Victoria, 1990

Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings Of Sea Country, Buku Larrnggay Mulka, Jennifer Isaacs Publishing, 1999

Wells, A., This is their Dreaming, University of Queensland, 1971

West, Margie (ed.), Yalangbara: art of the Djang’kawu, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2008

Yirrkala Film Project, Film Australia, 1981-95

Williams, Nancy, Australian Aboriginal Art at Yirrkala: Introduction and Development of Marketing, In Nelson Graburn (ed) Ethnic and Tourist Arts: Cultural expressions from the Fourth World, University of California Press, 1976 p266-284

Foot Notes

1. The legal concept, that Australia was ‘unoccupied country’ before colonisation. ↩

2. The term that Aboriginal people of Central and Eastern Arnhem Land use, to refer to themselves. ↩