Covering West Australia’s ‘Top End’, the Kimberley region embraces an area over 400,000 square km, taking in all country north of the vast spaces of the Great Sandy and Tanami Deserts. Situated on the west coast is Broome, famed ‘Port of Pearls’; Derby, ‘Gateway to the Ranges’, which borders the eastern margin of King Sound. On the eastern margin of the Kimberley, from north to south are situated Wyndham, Kununurra, and Halls Creek, all a short distance from the Northern Territory border and the mighty Victoria River Basin.

Image: View of Kununurra, Western Australia

The topography of the Kimberley is varied. Arid desert covers the southern aspects of the region and runs to meet the coast along the Eighty-Mile Beach. The red sand Pindan country dominates the coast here extending northwards along the Dampierland Peninsula to Cape Leveque. Held cradled between the arms of the Fitzroy and Ord River systems is the massive and ancient Kimberley plateau. Edged by a rugged coastline of drowned valley systems, cut by deep gorges and studded with islands. Inland the sandstone is also dissected by deep valleys and gorges and pierced by imposing outcrops containing caves and overhangs. The river systems of the sandstone plateau are punctuated by impressive falls and quiet pools as they flow to the sea. In the east Kimberley are the World Heritage listed Bungles Bungles and the impressive Ord River.

Language and Clans

There are five distinct cultural areas which include the Central and Northern Kimberley (Worrorra, Wunumbal and Ngarinyin); the Dampier Land Peninsula and the coast south of Broome to the West; the Ord River basin and drainage basins east to the Northern Territory; Halls Creek and the south-east region and the southern area comprising the land along the Fitzroy River south to the Great Sandy Desert. The region has been home to some twenty-seven distinct language groups.1

History

Whilst Aboriginal people have occupied the Kimberley for many thousands of years, non-Aboriginals did not occupy the area until the nineteenth century. The first exploration of the region by Anglo-Celtics was during 1837-8 by Captain George Grey, a British military officer.  However, Abel Tasman, and later William Dampier, were to record coastal features in the seventeenth century, with the latter camping in the area of One Arm Point in 1688. In the 1850s, European and Asian interests set up their own pearling industry and the pastoral industry was thriving by the end of the nineteenth century.

However, Abel Tasman, and later William Dampier, were to record coastal features in the seventeenth century, with the latter camping in the area of One Arm Point in 1688. In the 1850s, European and Asian interests set up their own pearling industry and the pastoral industry was thriving by the end of the nineteenth century.

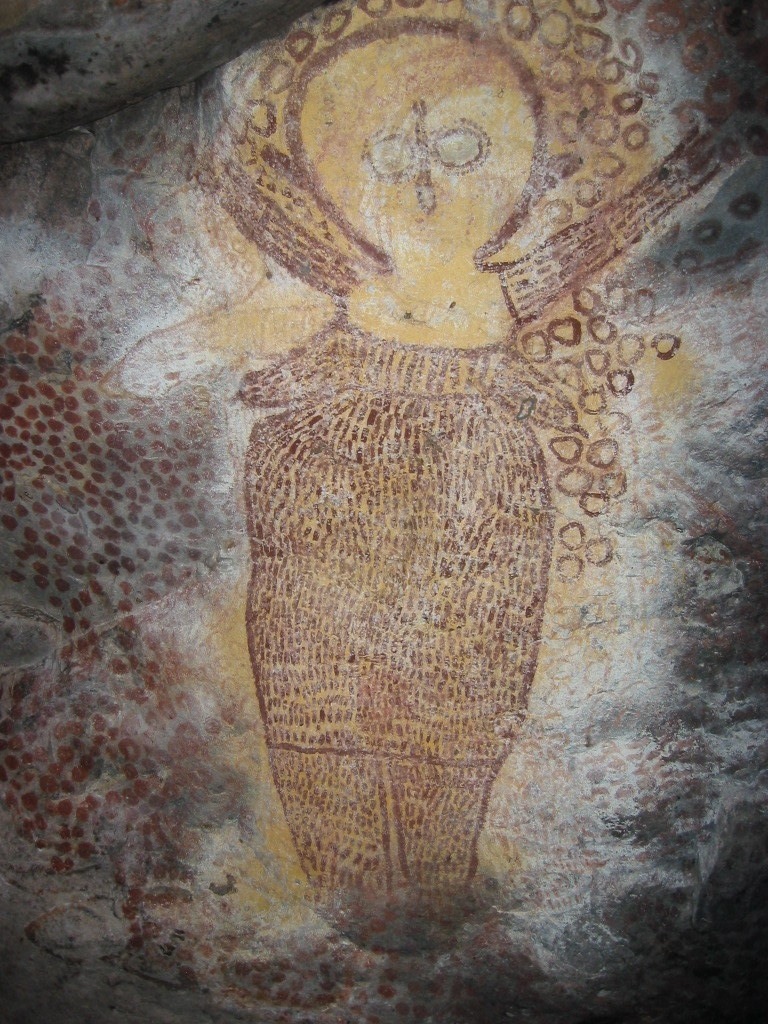

Image: Wanjina rock art, The Kimberley, Western Australia

Art and the Art Centre

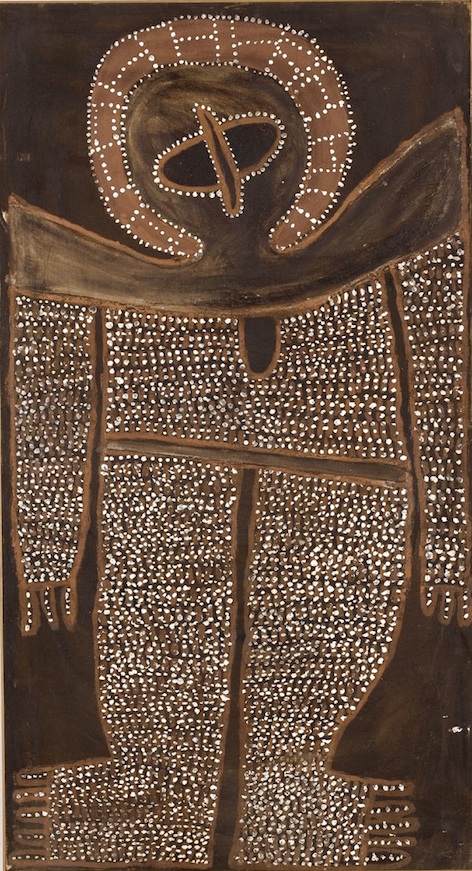

The ancient rock art of the Kimberley is world renowned. The Northern and Central regions are the lands of the Wanjina (also Wandjina) Beings and the earlier Gwion-gwion or Bradshaw paintings. Wanjina is a collective term for ancestral beings said to have emerged from the sea or descended from the sky. Wanjina are usually depicted in human form with white faces and bodies, with large round black eyes and no mouth, surrounded by a halo representing storm clouds, rain and lightning. An oval shape on the breast is thought to represent a pearl shell pendant typical of this region, but may also represent the heart or sternum.

The Wanjina shaped the landscape and control the elements, particularly by bringing the rain, and thus maintaining the cycles of nature and life; they are the harbingers of the wet season – when the tempestuous monsoonal rains refresh the parched land. The impressive and ancient rock figures are conserved and tended by their human descendants through ceremony and art, ensuring the continuation of their influence. These powerful spirit beings were painted on rock and in recent times on bark, and are a common theme in the work of contemporary artists of the Kimberley.

Wanjina are generally to be found painted in caves and shelters associated with the Wunambul, Worrorra and Ngarinyin people. The better-known paintings are concentrated within the gorges around the Gibb River, the Mitchell Plateau and the Drysdale River National Park.

The term Gwion-gwion or Bradshaw style covers a range of recognised sub-styles that range in size and complexity. Many are small monochromatic red oxide figures; others may have been painted in two or more colours. All are gracefully elegant and resemble a more languorous version of the Dynamic style rock paintings of Western and Central Arnhem Land. These elegant figures, often depicted with complex headdresses and other accoutrements such as tasselled belts and armbands, were first named after the explorer Joseph Bradshaw, who discovered them in 1891. Now the use of the term Gwion-gwion is becoming more commonly used. The name Gwion-gwion refers to the Sandstone Shrike-thrush – a small bird that in some areas was said to have painted the figures using blood from its beak.

Whilst there is a strong rock art tradition, painting on bark was not as prevalent in the Kimberley as it is among the people of Arnhem Land. Kimberley artists were first recorded painting on bark and board in the late 1930s. They were encouraged to produce work on transportable materials for the Reverend J.R.B. Love and anthropologists such as Helmut Petri and Arthur Capell to satisfy the growing interest in the art of the region. However, Kim Akerman states that early records of Kimberley performances, both sacred and secular, show that associated objects and sculptural forms also played an important role in some of the dancing.2 These include anthropomorphic carvings of ancestral beings.

Pearl shells are particularly distinctive to the Kimberley, being linked with personal adornment and spiritual powers, including rainmaking and ceremonies. In its natural state, the pearl shell with its brilliant lustre is associated with Unggud(the Rainbow Serpent). The shells were also traded locally and ultimately filtered across much of the continent.3

In the West Kimberley Ngarinyin artist Jack Wherra’s carved boab nuts were highly sought after, dense with narratives of bush-life, pastoral experiences, and the burgeoning fringe dweller existence. He produced a huge body of work between the 1950s and his death in the 1980s. Boab nuts were a favourite medium for artists as tourism gradually developed within the region. In the 1950s Bardi artist Bonny Sampi and others including Butcher Joe Nangan, a Nyikina man, started carving and painting boab nuts. These craft objects, unique to the Kimberley, became popular in the 1960s and were prized by tourists, becoming an important source of income for the artists around Derby. A substantial collection of decorated boab nuts are housed in the Western Australian Museum.

The most influential and instrumental person in regard to the development of art within the Kimberley, was Mary Macha,4 who encouraged, amongst others, Alec Mingelmanganu; Butcher Joe Nangan, who was now depicting the mythology and history of the region in striking watercolours and in carved pearl shell; and Rover Thomas.

Image: ALEC MINGELMANGANU 1910-1981, Wandjina, 1980, natural earth pigments and natural binder on canvas, © the artist’s estate

Cyclone Tracey, which wreaked havoc in and around Darwin on Christmas Eve 1974, was to have a profound effect on Aboriginal societies throughout Northern Australia. Senior Aboriginals collectively and individually, sought to interpret the event. Within the Kimberley, senior men regarded as ‘knowledgeable’ are said to have witnessed the event by mamarrarra (dream travelling). It would appear that there was a general consensus that in interpreting the events of Cyclone Tracy, the ‘knowledgeable men’ had reached the conclusion that the cyclone was the Rainbow Serpent, who was disturbed by the decline of traditional cultural activities and spiritual responsibilities by Aboriginal people.

The ‘knowledgeable’ believed that the Rainbow Serpent chose Darwin as its focus, being both the largest centre of European culture in the north as well as the largest population of Aboriginal people, who were considered to have lost the ‘law’. Soon after, two Kimberley men received dream visitations from the spirits of dead relatives. Firstly, Geoffrey Mangalamarra from Kalumburu in the far north Kimberley was given in a dream, the songs and dances of Cyclone Tracy palga (narrative dance cycle), which he orchestrated to be performed at communities throughout the Kimberley. A feature of the song and dance sequence were large painted emblems carried in the hands or across the shoulders of the dancers which incorporated panels representing the Unggud (the Rainbow Serpent) responsible and a threaded string figure of the ancestral Wanjina as a serpent, as well. Also, the starkly painted spectacular image – a ‘map’ of Darwin with the threatening and hovering cyclone and at the same time a cliff on the Isle of the Dead.

At the same time that Mangalamarra received his dream, so did Rover Thomas, in the Warmun community (also known as Turkey Creek) in the East Kimberley. Turkey Creek had become a haven for Aboriginal people, many of whom were driven off their country, with memories of massacres by pastoralists, and with the introduction of equal pay for Aboriginal workers in 1965.

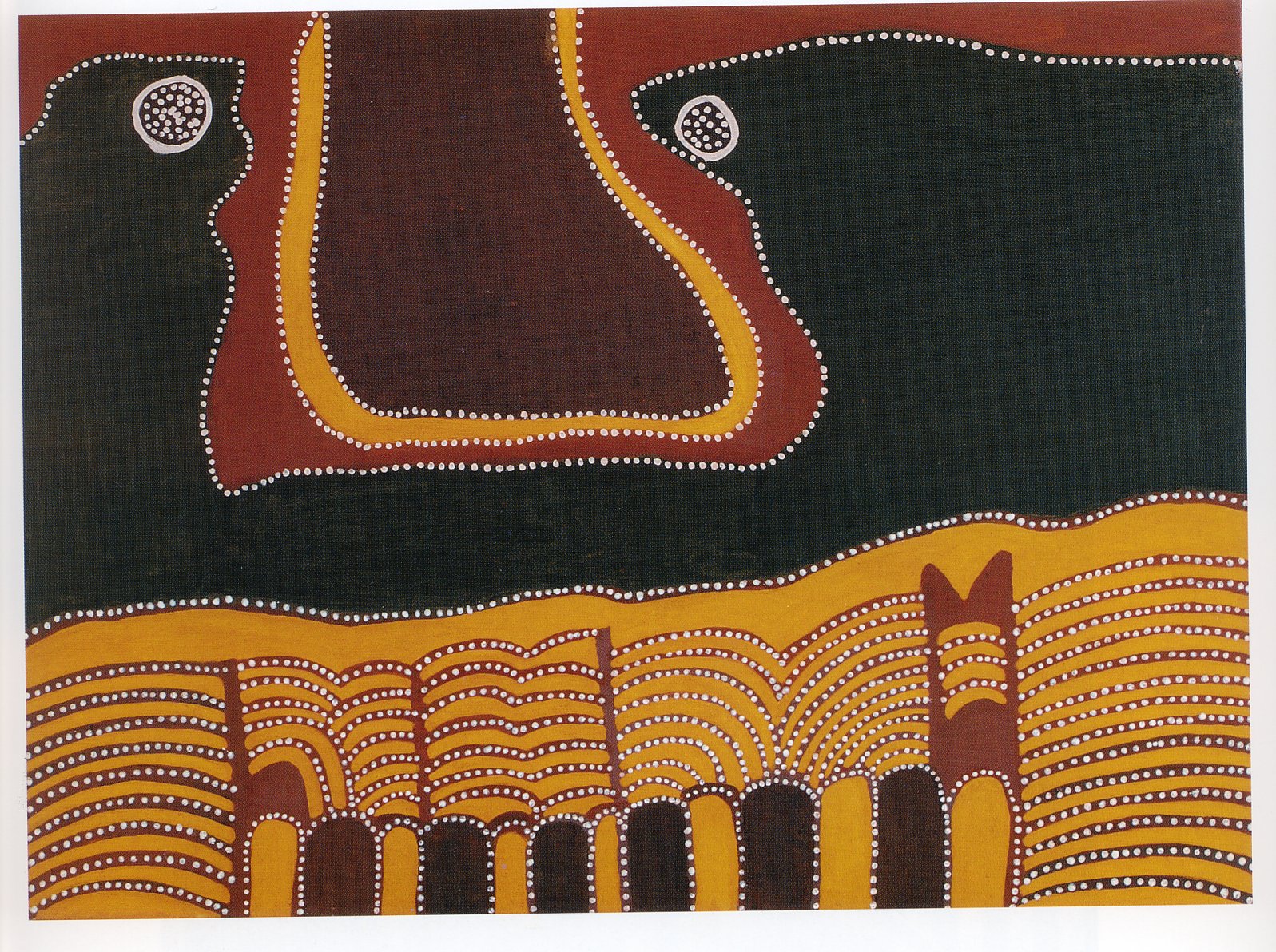

Image: ROVER THOMAS c.1926-1998, Dreamtime Story of Blue Tongue Lizard 1989, earth pigment and gum on canvas, © the artist’s estate

Thomas received a visitation from the spirit of a woman who died while being airlifted to hospital following a car accident. This woman was a classificatory mother of Rover Thomas and the accident occurred as a result of the car in which she was travelling overturning on a road flooded by a torrential wet season deluge. A Rainbow Serpent, a Wungurr known as Juntarkal, whose influence is felt across the East Kimberley into the Northern Territory, was believed to have caused her death.

Rover Thomas received many visitations from his ‘aunty’s’ spirit, in which she transmitted to him the details of the travels made by her spirit after her death and associated songs and paintings or dance emblems. One particular song referred to the observation of the Rainbow Serpent in the form of Cyclone Tracy, destroying Darwin. This cycle of songs and dances created by Thomas is known as the Kuril Kuril.5 Important elements of the ceremony, were a number of painted boards rested on the shoulders of the dancers, on which images of various sites and beings encountered by the woman’s spirit as she travelled, were depicted. Under Thomas’s direction, Paddy Jaminji, Thomas’s ‘uncle’, and a number of other men at Turkey Creek, created the initial boards used in the Gurirr Gurirr. Jaminji continued painting in this vein until 1981 when his failing eyesight forced him to stop. It was at this time that Rover Thomas commenced painting.

What followed was a renaissance throughout the Kimberley in traditional ceremonial life, with more frequent meetings concerning compliance to ‘law’ and ‘culture.’ The first time the Gurirr Gurirr paintings were shown to the broader community was in 1980 and these soon became sought after by collectors, museums and galleries. The art is a powerful form of modern ochre painting, completely different from the dot style developed in the central desert area and the Wanjina art of the adjacent central Kimberley.  In, what has become known as the Warmun, or East Kimberley School of painting. Topography and events are often shown in both plan and profile, with features usually presented as large blocks of colour, often outlined by a single border of white stippling, such as Jack Britten’s Narragorriny Gorge 1998. In this regard the paintings reflect the influence of rock art styles seen in the Ord River and adjacent Victoria River basins.

In, what has become known as the Warmun, or East Kimberley School of painting. Topography and events are often shown in both plan and profile, with features usually presented as large blocks of colour, often outlined by a single border of white stippling, such as Jack Britten’s Narragorriny Gorge 1998. In this regard the paintings reflect the influence of rock art styles seen in the Ord River and adjacent Victoria River basins.

Image: JACK BRITTEN (JOOALMA) 1921–2002, Narragorriny Gorge 1998, earth pigments on canvas © the artist’s estate

Initially the artists of Turkey Creek painted on any materials they could glean from their environment – pieces of tin, plywood, cardboard, old doors – much of it scavenged from the local rubbish dump. Many of the early paintings were carefully stored for display and use in ceremonies.

In 1979, a Bough Shed School was established so that the children would learn traditional culture and participate in the local language maintenance program. It was here that the artists brought their paintings to display them and tell their stories, which resulted in the Turkey Creek collection. The community is largely Catholic and many of the artists imbue their art with such imagery as The Young Joseph and Mary and Christ and the Battle as well as events relating to local history and mythology.

At Balgo located on the northeast fringe of the Great Sandy Desert in Western Australia, a strengthening of the art traditions of painting and sculpture also occurred. Balgo was initially established in 1939 by Pallotine priests, with the aim of creating a buffer community for the Aboriginal people of the desert and the expanding pastoral industry. Balgo, now also referred to as Wirrimanu, came under Aboriginal control in 1981. Since the early 1980s, recognition of the work of the artists has grown, with a solo exhibition in 1986 at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, and the Warlayirti Arts Centre being established in 1987. More recently a number of artists associated with Walyirti contributed to the blockbuster Canning Stock Route exhibition from the National Museum of Australia.

The Balgo community, unlike that at Warmun, did not follow the ochre tradition; instead its art evolved from familial links with the Pintupi, whose Central Desert Papunya community started painting with acrylics in the early 1970s. Since the introduction of acrylic and canvas to Balgo in the mid-1980s, the area has seen an explosion of thick, brightly coloured paintings that continue to be produced in the region today. The earlier influence of the Catholic Church can be seen in the imagery of some artists. A series of banners created in the early 1980s for the Catholic Church and exhibited within the Balgo Church, depict a cross-fertilisation of Aboriginal and Christian images. Individuality is clearly expressed by the majority of artists and a consistent vibrancy is evident in the majority of works. In recent times a new building was constructed to replace the old art centre, decorated with brightly coloured yellow, white and blue walls, vividly reflecting the hues of the artworks that created there.

Fitzroy Crossing, located in the Southern Kimberley, takes its name from the cemented boulder crossing of the Fitzroy River. It is a small centre supporting the nearby cattle stations and has a congregation of ten different language groups. The original landowners were River people. However due to the expansion of the pastoral industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the River people suffered and declined markedly, right into the 1930s. The void created as a result of this decimation, came to be filled by desert people who had drifted and who also found work on the cattle stations. As with Aboriginal pastoral workers in other parts of the Kimberley, the 1967 Equal Wage determination handed down by the High Court resulted in Aboriginal workers and their families being forced off the stations. Government reserves, and the presence of a mission station, ensured that Fitzroy Crossing became the major population centre, made up of a number of different language groups. Missionaries managed to moderate some of the violence and oppression, but in offering hope of a new order and beliefs, encouraged Aboriginal people associated with them to forego their culture and religious beliefs. However, with cultural reinforcement from more traditionally oriented neighbouring groups many cultural activities continue into the twenty-first century. While some artwork was produced prior to the 1980s, it was the development of the Mangkaja Art Centre that really allowed the creative abilities of both younger and older artists to develop. As with other art centres, works produced at Mangkaja appear to have evolved in their own manner – but like that of Walyirti cannot be stereotyped.

Further References

Aboriginal Desert Women’s Law: works by the Manungka Manungka Association from Balgo in the East Kimberleys, Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, 1994.

Akerman, Kim, Western Australia: A Focus on Recent Development in the East Kimberley, in Caruana. Wally, (ed.) Windows on the Dreaming; Aboriginal Paintings in the Australian National Gallery, Ellsyd Press, 1989.

Akerman, Kim, Rover Thomas and Warmun Art, in Diggins, Lauraine (ed.) A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, Malakoff Fine Art Press, Melbourne, 1989

Caruana, Wally, Aboriginal Art, Thames & Hudson, London, 1993, see chapter 4

Crawford, I., The Art of the Wandjina, Oxford University Press, 1968

Crumlin, Rosemary, Aboriginal Art and Sprituality, Harper Collins Publishers, Melbourne, 1991.

Gilchrist, Stephen, ‘Voices in Land: Art of the Kimberley’, in Ryan, Judith (ed), Land Marks, National Gallery of Victoria, 2006

Diggins, L. (ed), A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, Malakoff Fine Art Press, 1989, pp. 86-99

Field, Jennifer Joi, Written in the Land: the life of Queenie McKenzie, Melbourne Books, 2008

Isaacs, Jennifer, Spirit Country: Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art, Hardie Grant Books, 1999, see pp109- 119

Kleinert, Sylvia & Neale, Margo (general eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp.226 – 239

Paddy Bedford, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 2006

Perkins, Hetti & West, Margie (eds.), One Sun One Moon: Aboriginal Art In Australia, The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2000

Roads Cross The Paintings of Rover Thomas, National Gallery of Australia, 1994

Ryan, Judith, Images of Power: Aboriginal Art of the Kimberley, National Gallery of Victoria, 1993

Tacon, Paul, ‘Enduring Rock Art: Ancient Traditions, Contemporary Expressions’, in Ryan, Judith (ed), Land Marks, National Gallery of Victoria, 2006

Stanton, J. E., Painting the Country: contemporary Aboriginal art from the Kimberley region, Western Australia, University of Western Australia Press, 1989

Watson, Christine ‘Whole Lot, Now: Colour Dynamics in Balgo Art’, in Ryan, Judith (ed), Colour Power: Aboriginal art post 1984, National Gallery of Victoria, 2004