The development of Ramingining and Milingimbi are closely intertwined. Ramingining, in Central Arnhem Land, is located some 580 kilometres east of Darwin, west of the Glyde River, between the Woolen and Blyth Rivers and 435 kilometres by road west of Nhulunbuy. Milingimbi is an island community that forms part of the Crocodile Island Group in the Arafura Sea. The island is 440 kilometres east of Darwin and approximately half a kilometre off the mainland. The name Milingimbi is probably Djinan in origin, from the word Milininbi, literally meaning ‘the place where the well is’. There are a number of different clan groups within the population of some 1,000 people, including surrounding outstations.

Image: Aerial view of Ramingining, image courtesy of Bula’Bula Arts Centre, Northern Territory

The coastline near Milingimbi and Ramingining is comprised of alternating marshy mangroves and white sandy beaches. The inland border to this area is the fresh water Arafura Wetlands, a heritage listed area. A feature of the land as it rises from the coastal flood plains, which are covered in high lush grasses during the wet season, is an extensive eucalyptus forest, which is dotted with groves of monsoon rain forest and palm trees. The area is home to salt water crocodiles, water snakes and insect life. Further inland the Arafura Swamp dominates the landscape, and is a rich source of Barramundi and home to vast flocks of water birds, particularly gurrumartji (Magpie Goose).

Language and Clans

The two main languages at Milingimbi are Gupapuyngu and Djambarrpuyngu, although several other languages are spoken, while English is a second language for almost all Aboriginal residents. Originally the island was the territory of several Yan-nhanu speaking clans. The Wangurri, Gupapuyngu and Djambarrpuyngu clans that came from nearby Buckingham Bay, dominated the environment and it was from these groups that much of the art was generated. The Djadawitjibi people of the Djinang group has ownership of the land at the site of Ramingining, which is home to around 800 people, associated with 16 different clan groups, although this fluctuates particularly in the wet season. Djambarrpuyngu is the main language, though Dhuwala, Dhany’yi, Gupapuyngu, Ganalbingu, Liyagalawumirr, and Djinang are also spoken.

History

Explorers from China, Portugal, and Holland had visited Australian shores since the time of the European Renaissance. Macassan trepangers from Indonesia were regular and welcome visitors, camping at Milingimbi around the well, which is still referred to as the Macassan Well, and along the various beaches fronting the Arafura Sea. In 1901 with the formation of Federation, the government banned the visits from foreign neighbours, however the influence of the Macassans is still expressed through song and dance by several groups within the Ramingining area, especially by the Mildjingi and Ganalbingu clans.

In 1885 J.A. McCarthy established a cattle station at Murrwangi in the Arafura Swamp, which was to be an unsatisfactory experience for both the local Yolgnu and the cattleman, and the station was abandoned in 1907. Then, in 1923 a Methodist mission was established at Milingimbi. Milingimbi was bombed in World War II, forcing residents to Elcho Island and the mainland, and the island was used as an airforce base. The missionaries returned in 1951 and re-established the town, the church and a school. In the 1970s, administration of the area was passed to Milingimbi Community Incorporated. At the same time a community was established in Ramingining in the early 1970s.

Under Aboriginal Land Rights, a ‘sea closure’ is applicable to Milingimbi, the only place in the Northern Territory, extending two kilometres from the low water mark surrounding the island, which means permission is needed to enter.

Image: Ramingining from the air, image courtesy of Bula’Bula Arts Centre, Northern Territory.

The first European contact with bark painting can be traced to the 1923 British Museum expedition to collect specimens of flora and fauna. Setting up camp in the upper reaches of the Arafura Swamp, a place some 100 kilometres south west from the present Ramingining township, the party had come across X-ray style ochre paintings on the inside walls of a bark shelter.

More recently, the widely celebrated film Ten Canoes, depicted traditional Indigenous culture, lifestyle and language of the land and people of and around the Arafura Swamp and Ramingining.

Art and the Art Centres

Milingimbi

Milingimbi enjoys a long tradition of creative and cultural works – bark paintings, carvings and weavings. Bark painting has a tradition stretching back thousands of years, long before the arrival of Europeans. It is understood that balanda1 commissioned barks as early as 1912, and barks were collected during the 1920s from the time the first missionaries arrived, with the Methodist Overseas Mission being established in 1923. Although some missionaries encouraged the artists in the creation of art and craft as a commercial activity, it was not until the 1960s that the creation of bark painting would become a major source of rupia (income).2 Many of Milingimbi’s artists, both past and present, are represented in major international and Australian collections including the Kluge-Ruhe Collection and the Louis Allen Collection, which is now in the Art Gallery of Western Australia.

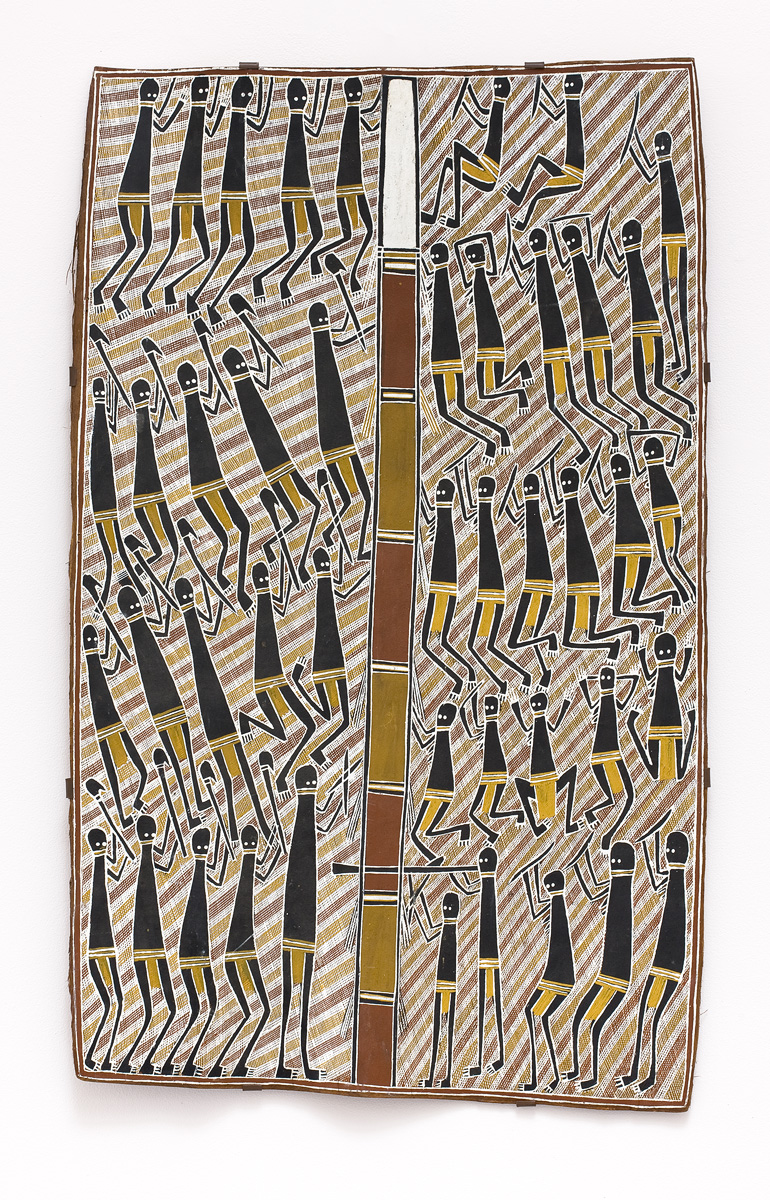

Image: GEORGE MILPURRURRU 1934-1998, Marradjirri Ceremony, natural pigments on bark, permission for the limited use of this image has been granted by Bula’bula Arts on behalf of Robyn Djunginy and the family of George Milpurrurru.

There was a continual movement of Aboriginal people from the mainland, as people attended ceremonies and traded. Different styles of painting developed as a result of the tutelage from some of the master painters. Single men who worked for the mission shared accommodation and introduced different concepts, while some artists were attracted by the new government establishment at Maningrida to the west.

With the knowledge that much of the paintings being created in the 1960s were for non-aboriginal audiences, many artists had been painting on a more commercial basis, resulting in artwork that reflected outside influences, changing aesthetics and political structure within Yolgnu society.

Of interest is the direction taken by those who influenced the commercial production of bark painting. There was an overriding direction to produce “suitcase” sized objects and barks to satisfy the tourist demand and while this contributed to the welfare of artists at the time, the legacy of small paintings over such a sustained period, may be questioned. Artists on the mainland, including David Malangi and George Milpurrurru, railed against the direction to paint small, believing that they were restricted in creating imagery that told their stories with integrity.

Particularly in the 1960s, collectors were drawn to the region, often seeking what was considered the “authentic” or cultural pieces that had a purpose in ceremonies. American collectors included Ed Ruhe and Louis Allen, both bought widely. Most of Louis Allen’s collection was acquired by the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 1990, and Ruhe’s collection, together with that of John Kluge, are jointly held by the University of Virginia. Amongst the many significant stories of the area, is the Wagilag Sisters ancestral story.

Ramingining

Unlike Milingimbi, there is little evidence of active art creation and collection within the Ramingining area in the period prior to the establishment of the art centre.

In 1977 the Australia Council funded an arts advisor position at Ramingining, providing a new focus for artists who had previously sold works through the Methodist Mission at Milingimbi.

Image: PETER MONDJINJU c.1928-1995, Birrkili Dreaming c.1969, natural pigments on bark, 66 x 44 cm © the artist’s estate

Djon Mundine became the art advisor in 1983. Perhaps the most significant undertaking for the new art centre was the American collector John Kluge’s commission, which resulted in the development of new and younger artists, as well as a platform for important painters such as Paddy Dhathangu who were in the twilight period of their lives. Many exemplary large barks were created, some focusing on the Dhuwa Honey Story Yarrpany. The story centres on the honey spirit in the form of a man who had many different names and came from the east near Blue Mud Bay, Gulf of Carpentaria, leaving dances, songs and language as he travelled, collecting honey along the way. The story nearly always features the cutting down of a tree to collect the honey and depending upon the location, gives rise to the formation of a river or to the frill-necked lizard or to rocks.3

In 1987-88, artists at the Ramingining art centre, created the seminal The Aboriginal Memorial: 200 hollow log funeral poles, representing two hundred years of European settlement in Australia which was acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

Image: Bula’Bula Arts Centre, image courtesy of Bula’Bula Arts Centre, Northern Territory

In the early 1990s, the art centre, Bula’Bula Arts, became independent. The centre’s name translates literally as ‘the tongue or voice of the Kangaroo’, referencing Garrtjambal the Red Kangaroo ancestor. Garrtjambal travelled from the Roper River to the Ramingining region and his journey links the groups of this area.

In 1997, an historic meeting was held at Ramingining attended by 32 artists, traditional owners and custodians for the purpose of discussing the manner in which the artists wanted their art shown publicly. The exhibition, The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters Story 1937-1997, to be held at the National Gallery of Australia later that year, contained a certain set of sculptures, which were sacred in nature. The Aboriginal peoples’ debate concerned whether these sculptures should be shown to an uninitiated audience. The issue, as expressed by Gawirriny Gumana, concerned the boundary between what objects were made and used in the private and ritual life, as against these same objects being called ‘art’ in the public arena.4

The Wagilag Sisters

The Wagilag narrative, is celebrated in a number of significant ceremonies by Dhuwa moiety groups across Central and Eastern Arnhem Land. The narrative relates the encounter between human and animal ancestors and provides a basis for key aspects of Yolngu laws relating to authority, kinship, territory and marriage. It also tells of the first monsoon and the flooding of the earth.

The story covers the land of several clans, and in particular the waterhole named Mirarrmina on the Upper Woolen River in Liyagalawumirr country. Mirarrmina is the home of Yurlunggurr, the giant olive python, who is a very powerful ancestor spirit.

Each clan has its version of the story that concerns two sisters who journeyed from the land of the Marrakulu on the east coast of Arnhem Land, where the Sisters have had irregular relations with their kinsmen and are forced to flee.5 They camp by the waterhole. One sister has a child and the younger sister, who is pregnant, gives birth. The Sisters are unaware that the waterhole is the sacred home of Yurlunggurr, who is angered as a result of one of the sisters entering the waterhole and polluting it. The Sisters make camp, build a bark hut and try to cook food they have caught and collected on their journey. However, things start to go wrong – the animals and plants come to life and leap out of the fire and run into the waterhole, disturbing the python even further.

Yurlunggurr emerges from the waterhole and rises into the sky, creating the storm clouds and thunder and lightning of the first monsoon. The Sisters perform songs and dances to stop the flood of rain, and to deter the python’s anger, but to no avail. Exhausted, the women collapse and the python descends and swallows the Sisters and their children.

Soon afterwards the python develops a terrible stomach ache because he has eaten beings that belong to the same moiety as himself. The pain becomes so great that he vomits the Sisters back out. (He retains the children as they belong to the opposite moiety, the Yirritja). The Sisters are brought back to life by the bites of stinging caterpillars, and then the python beats them with clapsticks (malirri) and swallows them again.

The Sisters’ clansmen have been following them, and that night they camp on the site where the Sisters disappeared. During the night, the Sisters come to them in their dreams and reveal the secrets of the sacred dances they had performed in efforts to stop the rain.

There is a difference in the spelling of the Wagilag depending on the clan and language group, with Wagiluk applicable to the eastern clans.

Artists: Past and present

| Jimmy Wululu | Micky Durrng Garrawurra | |

| Dorothy Djukulul | Namiyal Bopirri | |

| George Milpurrurru | David Malangi | |

| Paddy Dhathangu | Andrew Marrgululu | |

| Jimmy Moduk | Ronnie Djanbardi | |

| Djardie Ashley | Johnny Liwangu | |

| Clara Wubugwubuk | Albert Djiwada | |

| Dawidi Djulwak | Philip Gudthaykudthay | |

| Peter Bandjuljul | Jack Wunuwun | |

| Charlie Boyun | John Bulunbulun | |

| Samuel Lipundja | Tom Liyadarri | |

| Norman Mangawila | Fred Nangananarrlil |

Further References

Caruana, Wally, ‘Wagilak and Kjang’kawu’, in Art From Land: dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal art, Morphy, Howard and Smith Boles, Margo (ed.), University of Virginia, 1999

Caruana, Wally & Nigel Lendon (eds.), The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters Story 1937 – 1997, National Gallery of Australia, 1997

Diggins, Lauraine, (ed), A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, Malakoff Fine Art Press, 1989, pp. 15 – 39

Isaacs, Jennifer, Spirit Country: Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art, Hardie Grant Books, 1999, p.162

Kleinert, Sylvia & Neale, Margo (general eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000, p.550

Mundine, Djon, ‘The Land is Full of Signs’, in Art From Land: dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal art, Morphy, Howard and Smith Boles, Margo (ed.), University of Virginia, 1999

Murphy, Bernice (ed), The Native Born: Objects and representations from Ramingining, Arnhem Land, Museum of Contemporary Art, 1996

Ryan, Judith, Spirit in Land: Bark Paintings From Arnhem Land, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1990

eastarnhem.nt.gov.au

Foot Notes

1. Word for non-indigenous people. ↩

2. Many words from Macassan influence have been incorporated into various Yolngu languages. ↩

3. Mundine, Djon, ‘The Land is Full of Signs’, in Art From Land: dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal art, Morphy, Howard and Smith Boles, Margo (ed.), University of Virginia, 1999. ↩

4. Caruana, Wally, ‘Wagilak and Djang’kawu’ in Art and the Land: dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal art, pp121. ↩

5. Ibid p125. ↩