The term ‘urban’ art mainly refers to artists working in major capital cities and within the general Australian contemporary arts scene, as opposed to those in Aboriginal communities, who may be seen working in a more ‘traditional’ framework. Much urban art deals with social and cultural issues and makes important political statements focussing on, for example, the stolen generation, land rights, and reconciliation. There also tends to be a probing nature to the art: a questioning of identity or a challenge to colonial accounts of Australian history. ‘Urban’ art is often provocative, confronting, humorous and playful. Those artists under the umbrella of ‘urban’ art are both self-taught and professionally trained, and use multiple forms of media.

History

A greater level of interest and funding in Indigenous arts from the 1960s saw a rise in printmaking, photography, ceramics, and painting. The introduction of different materials, such as the watercolours in Hermannsburg, the use of acrylic (synthetic polymer) paint from the 1970s and the introduction of batik, contributed to a shift in Indigenous artists’ approach to their practice. There has also been a shift in Western attitude from understanding Aboriginal art as ethnographic material to recognition of its place on the international contemporary art stage.

The Koori Art exhibition held in 1984 at Contemporary Art Space in Sydney provided a focus for urban indigenous art, bringing together black artists who had been working in isolation but who had important common links. The exhibition also brought these artists to the attention of public art institutions. For some urban artists, the importance of travelling to Aboriginal communities, meeting with Aboriginal people and being exposed to a more traditional lifestyle has provided an important inspiration for their art.

The bicentennial of the official European landing in 1988 was celebrated as a nationwide commemorative event, although for Aboriginal people, the year was one of mourning. The cultural difference in the perception of this historic event was a watershed moment. Many city-based artists responded to this divergence and embraced different mediums to express their indictment of the European settlement of Australia.

Art and the Artists

Brisbane-born artist Tracey Moffatt (1960-) was a pioneer of photography and video art. She is one of Australia’s most internationally recognised artists. Her now iconic image Something More #1 1989, shows the artist in a torn red cheongsam dress in an outback colonial setting. In this series Moffatt references the dislocation and oppression of the colonised, and explores issues of race and gender in Australian history and society. Moffatt, like other artists of Indigenous-heritage such as Gordon Bennett, prefers to place her work more broadly in the context of Australian contemporary art.

Gordon Bennett (1955-) is an artist based in Brisbane, who works in the context of the postmodernist art movement. Bennett uses the postmodernist techniques of appropriation, irony and pastiche to comment on race relations in Australia. Bennett’s Australian Icon (Notes of Perception No. 6) 1989 is an early example of his iconic and celebrated style.

![]()

Image: GORDON BENNETT 1955-, Australian Icon (Notes on Perception No 6), 1989, synthetic polymer on canvas, © the artist

The series is a critical response to the Bicentennial celebrations in 1988. In particular, Bennett uses the image of the tall ship that sailed into Sydney Harbour in 1788, and again in 1988 as part of the Bicentennial celebrations, to comment of the Australian colonial identity. Such an image has entered the collective unconscious of Australian identity, reinforced in its representation in social history books. The inversion of colour and space of the painting inverts the romantic view of the explorers and colonists of the First Fleet arriving on Australia’s shores with the experience of the Aboriginal people viewing the approaching alien vessel. This difference of perception of imagery or an event is hinted to in the title. The ship is composed of a series of small dots – almost like pixels – which further deny solidity to the symbol of the ship.

Queensland

Richard Bell (1953-), also based in Queensland, uses wordplay and graffiti imagery to comment on race relations, Indigenous society and questions the materialistic framework of contemporary Indigenous art. His painting, Scientia e metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem), which won the 2005 Telstra Painting Award, comments directly on the latter issue. The work is emblazoned with the words ‘Aboriginal art it’s a White Thing’ over a background of appropriated colour field painting and partially obscured by Jackson Pollock style paint splashes. The painting directly references the control of the marketing and presentation of Indigenous culture by non-Indigenous art professionals.

Another Queensland-based artist, Daniel Boyd (1982-), uses similar juxtaposition of text and colour in Treasure Island 2005. The painting appropriates the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies’ map of language groups in Australia with the words ‘Treasure Island’ in cursive script across the land.  Boyd conflates the European scramble for unoccupied land (terra nullius) and the search for the fabled ‘Great Southern Land’ with the popular conception of buccaneers in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (first published in 1883). Boyd further explored the theme of piracy in his No Beard paintings produced in 2007. Boyd appropriated portraits of King George III and Governor Arthur Phillip, adding popular symbols of the pirate: parrot and eye patch. The expression ‘no beard’ refers to an account of Cook’s first landing in Australia, when, it is said, Aboriginal people thought he and his men were women, due to their lack of facial hair.

Boyd conflates the European scramble for unoccupied land (terra nullius) and the search for the fabled ‘Great Southern Land’ with the popular conception of buccaneers in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (first published in 1883). Boyd further explored the theme of piracy in his No Beard paintings produced in 2007. Boyd appropriated portraits of King George III and Governor Arthur Phillip, adding popular symbols of the pirate: parrot and eye patch. The expression ‘no beard’ refers to an account of Cook’s first landing in Australia, when, it is said, Aboriginal people thought he and his men were women, due to their lack of facial hair.

Thancoupie Gloria Fletcher James (1937-2011), also known as Thanakapi, is widely credited as the founder of the Indigenous ceramics movement in Australia. She trained under the famed Australian ceramicist, Peter Rushforth, and the Japanese potter Shiga Shigeo. The decoration on her pieces relate to traditional storytelling but her focus was always primarily on the ‘object as art’ in the Western tradition.

Image: THANAKUPI (1937-2011), Mosquito Corroboree 2002, narrow-necked stoneware pot © the artist’s estate

Victoria

In Victoria, the contemporary painting movement was spearheaded by Lin Onus (1948-96) working in the 1980s and 1990s. Onus found inspiration in a range of artistic practices including Arnhem Land bark painting. The mixed media work, Fire 2, uses a combination of traditional and modern techniques: including synthetic polymer paint, bark and feathers. The work depicts a forest with trees marked by traditional rarrk painting, but has a viewpoint recognisable to Western art practice.

Image: LIN ONUS 1948-1996, Fire 2 1989, synthetic polymer on canvas, bark, and feathers on board © the artist’s estate

On several trips to northern Arnhem Land, Onus collected feathers, flowers, sand and bark that he incorporated into the painting. The subject itself is inspired by this trip also, where he observed bushland being burnt off to promote regeneration.

Fellow Victorian artist Vicki Couzens (1960-) is a Kirrae Wurrong woman from the Western District of Victoria whose practice focuses on the reinvigoration of traditional Indigenous art. Couzens felt an immediate and powerful connection upon viewing the Lake Condah possum skin cloak displayed at the Australian Print Workshop in Melbourne. Lake Condah is her Grandmother’s Country. Couzens was inspired to recreate a cloak using traditional methods, culminating in her first experience to replicate a cloak for the project ‘tooloyn koorrtakay-squaring skins for rugs’.

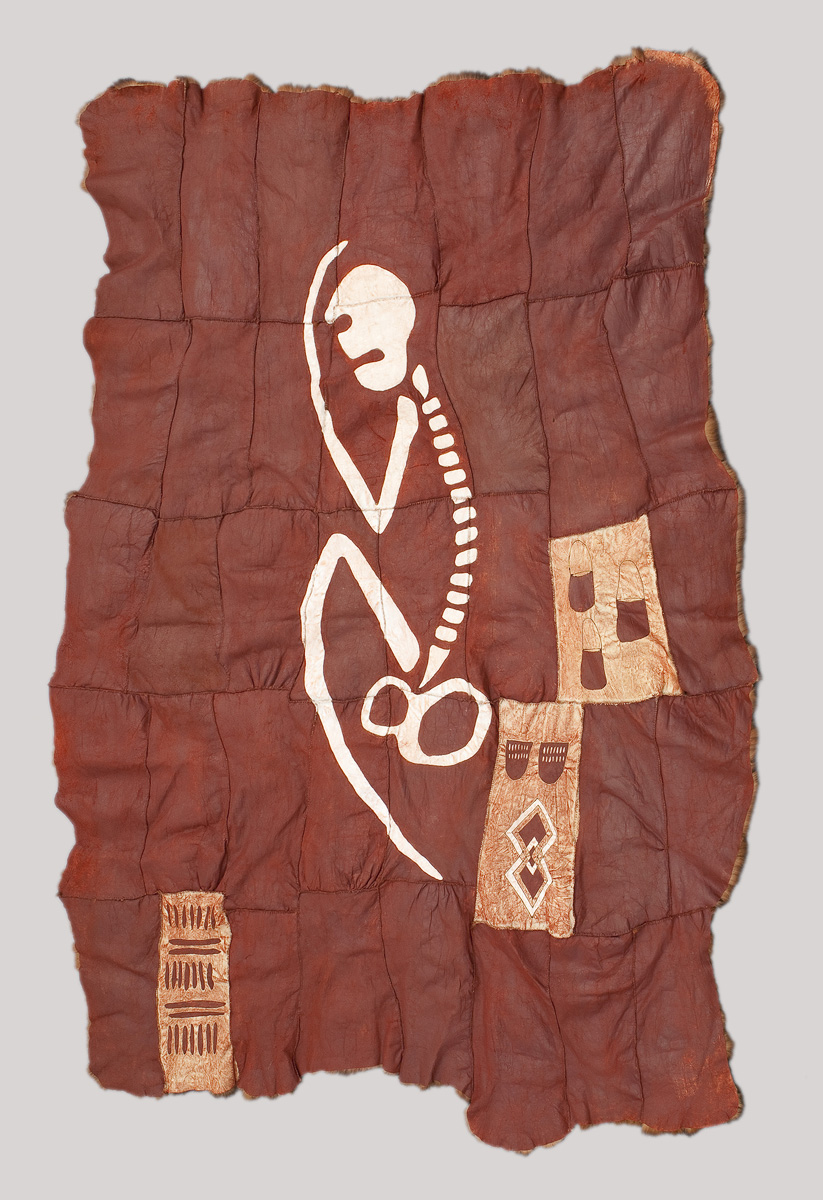

The Yaree Yareengu (to mourn) Yunggama cloak and its designs was created concerning the rituals and ceremonies of death. People were often buried with the possum skin cloaks, which explains why so few cloaks have survived into modern times. Couzens reclaims these original meanings with the inclusion of the outline of a figure, symbolically implicating the presence of a body. The three inlays of the interior of the cloak reference traditional possum skin bags (centre right), breasts and other symbols of women (bottom right) and marks of men’s ritual scarring used in ceremony and mourning (bottom left).

Image: VICKI COUZENS 1960 -, Yaree Yareengu (to mourn) Yunggama cloak, 2013, New Zealand possum skins, wax linen thread and pigment mixed with water and polyvinyl acetate © the artist

The creation of these possum skin cloaks represent the evolution in contemporary society of traditional cultural practices – and is concerned with exploring, relearning and invigorating of these practices.

Other Melbourne-based Indigenous artists, such as Christian Bumbarra Thompson (1978-) and Brook Andrew (1970-), use non-traditional mediums to explore and challenge conceptions of race and Australian history. Brook Andrew examines issues of indigenous male identity in his work Sexy and Dangerous, 1998. The work contrasts an anthropological photograph of an Aboriginal man with overlaid Mandarin script and the words ‘Sexy and Dangerous’. The work juxtaposes and explores nineteenth-century concepts of Aboriginality with contemporary stereotypes of Indigenous men.

South Australia

Adelaide-based Trevor Nickolls (1949-2012), using a more traditional painting practice, explores the meeting of Aboriginal and Western culture. In particular, his Dream Time Landscape adopts the Western postmodern conventions of quotation, by appropriating Western Desert imagery in the uses of dots. Much of his work is concerned with the alienation and despair of individuals within the urban landscape. The subjects and titles of his painting are polarised between themes of the ‘Dreamtime’ and the ‘Machinetime’. This painting in particular expresses Nickolls’ concern for the degradation of the land and the environment under white occupation.

Image: TREVOR NICKOLLS 1949-, Dream Time Landscape, 1989, synthetic polymer on canvas © the artist’s estate

Working in a similarly colourful and pictorial style in South Australian artist Ian Abdulla. His art depicts the landscape and activities of his hometown Swan Reach. His paintings have a strong storytelling element, juxtaposing text and image against a flattened foreground.

Western Australia

Christopher Pease (1969-), an artist based in Perth, explores questions of Nyoongar identity, creating imagery challenging the accepted Western version of Australian history and culture. In Freeway, there is a convergence of the familiar loops and whorls of a busy urban road network and the iconography and colour palette often associated with indigenous ochre painting. The aerial perspective of the urban landscape further emphasises the connection to traditional depictions of land.

Image: CHRISTOPHER PEASE 1969-, Freeway 2003, ochres and oil on canvas © the artist

Pease uses the traditional medium of ochre in the creation of this modern scene, fusing past and present Indigenous culture and identity into the canvas. Pease collected the ochre from an ochre pit at Wilsons Inlet, Denmark, Western Australia: “This ochre pit has been used by my family for generations and was formed by both tidal and meterological influences that moved sediment within water… All things mineral and organic (including ourselves) are controlled by the movement of our planet. In this way we are insignificant.”1

Pease describes that his artistic training in secondary school focused largely on Impressionism, the Heidelberg School and modernism: “Any lessons related to Aboriginal art were generic with no relationship to land/country. I associated concentric circles with Jasper Johns rather than Indigenous iconography. The rise of Boomalli and the so-called urban Indigenous artists of the 1980s was the point where Indigenous people who were not living ‘traditionally’ found a voice through non-traditional art.”2

Richard Bell, described the works of contemporary Indigenous artists as ‘creating the new Dreaming.3 This quote reflects the greatest strengths of contemporary Indigenous art practice: its diversity and adaptability. Urban Indigenous practice is either traditional in its forms or informed by traditional cultural practices, but always responsive to the immediate environment. This grounding in traditional and contemporary life has contributed to its success and renown both at a national and international level.

Artists: Past and Present

| Ian Abdulla | Vernon Ah Kee | Michael Aird | |

| Tony Albert | Shirley Amos | Brook Andrew | |

| Bronwyn Bancroft | Bianca Beetson | Richard Bell | |

| Gordon Bennett | Mervyn Bishop | Joshua Bonson | |

| Euphemia Bostock | Daniel Boyd | Jodie Broun | |

| Trevor ‘Turbo’ Brown | Kevin Butler | Robert Campbell Jnr | |

| Karen Casey | Craig Allan Charles | Christine Christophersen | |

| Lorraine Connelly-Northey | Vicki Couzens | Brenda L. Croft | |

| Nici Cumpston | Destiny Deacon | Julie Dowling | |

| Danny Eastwood | Andrea Fisher | Fiona Foley | |

| Jenny Fraser | Kerry Giles | Julie Gough | |

| Treanha Hamm | Jennifer Herd | Adam Hill | |

| Sandra Hill | Alice Hinton-Bateup | Gordon Hookey | |

| Sylvia Huege de Serville | Joe Hurst | Diane Jones | |

| Gary Jones | Jonathan Jones | Roy Kennedy | |

| Francine Kickett | Leah King-Smith | Yvonne Koolmatrie | |

| Lawrence Leslie | Irwin Lewis | Peta Lonsdale | |

| Janine McAullay Bott | Peter Yanada McKenzie | Gayle Maddigan | |

| Fernanda Martins | Ricky Maynard | Arone Raymond Meeks | |

| Danie Mellor | Lisa Ann Michi | Tracey Moffatt | |

| Archie Moore | Pauline Moran | Sally Morgan | |

| Clinton Nain | Joanne Currie Nalingu | Laurie Nelson | |

| Trevor Nickolls | Caroline Oakley | Lin Onus | |

| Tirik Onus | Christopher Pease | Nicole Phillips | |

| Shane Pickett | Avril Quaill | REA | |

| Adam Ridgeway | Michael Riley | Elaine Russell | |

| Jeffrey Samuels | Brenda Saunders (Palma) | Vincent Serico | |

| James Simon | Darren Siwes | Dorsey Smith | |

| Jake Soewardie | David Spearim (Fernando) | Gordon Syron | |

| Christian Bumbarra Thompson | Ian Waldron | Judy Watson | |

| Lilla Watson | Jason Wing | Yondee (Shane Hanson) |

Further References

Andrew, Brook, Eye to Eye, Monash University Museum of Art, 2008

Caruana, Wally, Aboriginal Art, Thames & Hudson, London, 2003

Croft, Brenda L., Indigenous Art: Art Gallery of Western Australia, Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2001

Diggins, L. (ed), A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art, Malakoff Fine Art Press, 1989, pp.125-137

Fox, S., and Maughan, J., Ian Abdulla: Elvis has entered the building, Wakefield Press, 2003

Gough, Julie, ‘Being There, Then and Now: Aspects of South-East Aboriginal Art’, in Ryan, Judith (ed), Land Marks, National Gallery of Victoria, 2006

Joss, Sandra Maya, Beyond the dreamings: Identity and representation in Australian Aboriginal urban art, Thesis (Ph.D.)–The American University, 2004.

Kleinert, Sylvia & Neale, Margo (general eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp180 – 196; pp.240 – 296

Leslie, Donna, Aboriginal Art: creativity and assimilation, Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2008

McCulloch, Susan, Contemporary Aboriginal Art: a guide to the rebirth of an ancient culture, Allen & Unwin, 2001

Neale, Margo; with contributions from Michael Eather … [et al.], Urban Dingo: the art and life of Lin Onus, 1948-1996, Craftsman House in association with the Queensland Art Gallery, 2000

Ryan, Judith (ed), Colour Power: Aboriginal art post 1984, National Gallery of Victoria, 2004

Story Place: Indigenous Art of Cape York and the Rainforest, Queensland Art Gallery, 2003

Thompson, Liz, Fighting for Survival: the Ngaanyatjarra of the Gibson Desert, J.B. Books Australia, 2000

Foot Notes

1. Christopher Pease, artist statement, 2006↩

2. Christopher Pease in Brenda Croft et al. Culture Warriors: National Indigenous Art Triennial, 1st ed, National Gallery of Australia, p. 143↩

3. ibid. ↩