The Tiwi Islands are 80 kilometres north of Darwin, where the Arafura and Timor Seas meet. They are comprised of Melville and Bathurst Islands and are Australia’s second and fifth largest islands respectively. The islands combined area over 8,000 square kilometres and are separated by the narrow Apsley Strait. The Tiwi Islands are heavily forested and host an abundance of native flora and fauna, including wallaby, possum, bandicoot, snake, lizard and numerous bird species. The coast changes from white sandy beaches, to mangrove swamps, to rocky outcrops and clay cliffs.

Image: The Tiwi Landscape © Tiwi Arts

The Tiwi Islands experience a monsoonal climate, which, combined with the islands’ isolation, means that they support a number of plant and animal species found nowhere else in the world. The islands have been occupied by the Tiwi people for at least the last 7,000 years. Currently the population is around 2,500, with most people living near the permanent settlements of Nguiu on Bathurst Island and Pirlangimpi and Milikapiti on Melville Island.

Language and Clans

Despite the closeness of the Tiwi Islands to the mainland, the Tiwi people are culturally and linguistically distinct from the clans of Arnhem Land. The word Tiwi means ‘human beings’ or ‘we the people’. The people who live on the Tiwi Islands have no name for their world, and they call the rest of the world ‘over there, on the other side of the water’. Historically, for the Tiwi, the two Islands were the whole and only world. Their art is cosmic, referring to sky, earth, air and sea, and the life and death of human existence.

These days the Tiwi feel that maintaining their language is vital if they are to retain their culture. Most Tiwi choose to speak to each other in their own language – Tiwi, rather than in English, their second language.

The skin group, or Yiminga of the Tiwi is matrilineal; it is inherited from the mother and determines the marriage line. The word Yiminga, means skin-group, totem, life, spirit, breath and pulse. There are four skin groups, namely; Wantarringuwi (meaning sun), Miyartiwi (pandanus), Marntimapila (stone), and Takaringuwi (mullet). The skin-group into which Tiwi is born determines whom they may and may not marry.

History

The Tiwi people interacted with Macassan traders well before the arrival of Westerners to Northern Australia. Dutch, French and British explorers and navigators visited throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Explorer Phillip Parker King visited Melville Island in 1818, and noted that the native people knew a number of Portuguese words, suggesting that Portuguese sailors also had spent time on Australia’s northern shores.

The first European settlement was established in September 1824 on Melville Islands at Fort Dundas, near present-day Pirlangimpi. This was the first British settlement in northern Australia, but was abandoned in 1829. In 1911, the South Australian Government gave 10,000 acres of land on Bathurst Island to the Catholic Church, to build a mission under the guidance of Father Francis Xavier Gsell, and the Islands were proclaimed an Aboriginal Reserve in 1912. A timber Catholic Church, built in the 1930s, still stands in Nguiu today. Today Tiwi culture is intermingled with Catholic symbols, evident in examples of Tiwi art. In 1978, ownership of Bathurst Island was returned to the Tiwi people.

Ceremony plays a vital role in Tiwi life and culture. As Tiwi culture is an oral one, traditions are not written down and can evolve and vary according to the circumstances of the time. The two most important cultural ceremonies in Tiwi are the Kulama ceremony, performed annually, and the Pukumani (mortuary) ceremony. The Kulama ceremony takes place at the end of the wet season. It is a celebration of fertility and life and involves three days of body painting, singing, dancing and eating yams.

The Tiwi bury their dead quickly after the life has left the body, but return to the gravesite to perform the rituals that help the spirit of the deceased return to its country. The Pukumani ceremony is performed six months after a person’s death, and is the most important ceremony in a person’s life in the land of the living. At the time of death the Mobuditi (spirit of the dead) is released from the body, but the person’s existence in the living world is not complete until the Pukamani ceremony has been performed.

The performance of this ceremony ensures that the mobuditi goes from the living world into the spirit world. Prior to the ceremony, surviving family members carve and decorate tall totemic poles, which are placed around the burial site during the ceremony. These poles symbolise the status and prestige of the deceased, as well as acting as territorial markers for the descendants of the person who has died. The Pukumani ceremony allows Tiwi full expression of their grief. It is a public ceremony and provides a forum for artistic expression through song, dance, sculpture and body painting.

The performance of this ceremony ensures that the mobuditi goes from the living world into the spirit world. Prior to the ceremony, surviving family members carve and decorate tall totemic poles, which are placed around the burial site during the ceremony. These poles symbolise the status and prestige of the deceased, as well as acting as territorial markers for the descendants of the person who has died. The Pukumani ceremony allows Tiwi full expression of their grief. It is a public ceremony and provides a forum for artistic expression through song, dance, sculpture and body painting.

Image: Axel Poignant 1906-1986, Pukamani Memorial Poles, Melville Island, Tiwi Islands, Northern Territory, October 1948, National Library of Australia PIC/14211/3 LOC

A striking difference between the Tiwi and mainland Aborigines, is an absence of division between the sexes in religion and ceremony. Among the Tiwi, no secret-sacred line excludes either men or women from religious activities. When occasion demands, a woman may perform the role of principal executive for a Pukamani, and women can, and do make mortuary poles.

Art and the Art Centres

Contemporary Tiwi artists draw on the elaborate decoration of traditional ceremonies, including painting patterns on the body, carving and decorating ceremonial hollow log funeral poles, the creation of elaborate head-dresses and other body adornments, weaving and printmaking borne from the tradition of ceremonial Pukamani poles.

The lexicon of symbolism in Tiwi art is not rigid or precise. For example, a circle can represent a fire or a meeting place, which is common, but can also represent the sun, or coral, or poisonous yams, or something else of the artist’s choosing. This fluidity of meaning is quite particular to the Tiwi Islands, where self-expression and personal nuance are admired and encouraged even in the application of traditional designs.

Kitty Kantilla (c.1928-2003) is the most highly acclaimed artist of the Tiwi Islands. She began making art in her fifties while living in the small community of Paru on Melville Island. She learned to carve with rudimentary tools, and began experimenting with painting in ochre. In 1989 she moved to Milikapiti where she developed a working relationship with the Jilamara Arts and Craft centre, which continued for the duration of her career. She worked professionally as an artist until the end of her life.

Kantilla’s oeuvre consists of painted works on bark, paper and canvas, as well as etchings and hand-carved ironwood sculptures. She worked consistently in the traditional Tiwi palette of deep red, milky white and golden yellow ochres, and expressed herself confidently, alternating between bold geometric forms and intimately delicate cross-hatching and dotting.  Her carvings were made without power tools, and the density of the ironwood made the working process both time consuming and physically very demanding.

Her carvings were made without power tools, and the density of the ironwood made the working process both time consuming and physically very demanding.

Thematically, she drew on Tiwi song and ceremony, and the landscapes and seascapes of the islands to inform her art-making process, which was at times, whimsical and at others, rigorously self-disciplined. She modestly described her own work as being pumpuni jilamar which means good design.

The artist Pedro Wonaeamirri is one of the leading artists of the younger generation of Tiwi Islander painters. He has been practicing as an artist since his late teens when he finished high school in Darwin, and works with traditional materials and designs (jilamara). He currently lives and works at Milikapti on Melville Island.

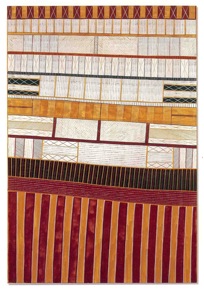

Image: PEDRO WONAEAMIRRI 1974- Pwoja, 2007, ochre on linen, © the artist

He learnt to paint under the guidance of his grandmother Jacinta Wonaeamirri, and produces work on bark, canvas, paper and carved wood. He is also known for his Pukamani poles, which he carves and paints by hand, both for traditional family ceremonies and for museums and galleries throughout Australia and internationally.

He uses natural ochres from Melville Island, which he applies with paintbrush and Pwoja, the traditional Tiwi painting comb made from blood wood or ironwood timber, to create the many lines and dots that form his intricately detailed works. The lines of the brush represent the miyinga (scars on the body) and the dots from the pwoja represent yirrinkiripwoja (body painting).

Wonaeamirri is also a traditional dancer and began taking part in ceremonial dances as a young child. He regularly performs at ceremonies and other important events. He focuses on honouring his ancestors and passing on Tiwi traditions to the younger generations.

There are three art centres on the Tiwi Islands: Jalimara Arts and Crafts Association, the Munupi Arts and Crafts Association on Melville Island, and Tiwi Design Aboriginal Corporation on Bathurst Island.

There are three art centres on the Tiwi Islands: Jalimara Arts and Crafts Association, the Munupi Arts and Crafts Association on Melville Island, and Tiwi Design Aboriginal Corporation on Bathurst Island.

Jilamara Arts & Crafts Association is located at Milikapiti (Snake Bay). The Tiwi word Jilamara, which roughly translates to design refers to the intricate ochre patterning traditionally applied to the bodies of dancers and the surface of carved poles during the Pukumani funeral ceremony.

Today artists at Jilamara work with a palette of natural ochres to produce paintings on linen, canvas, paper and bark. There is also a tradition of limited edition print production, including etchings, screen prints and lithographs. Many artists draw their inspiration from creation stories, clan totems, and ceremonial body paint and scarification designs.

Image: ARTIST UNKNOWN, Tiwi Female Figure c.1960, natural earth pigments on carved softwood

Munupi Arts & Crafts Association is located at Pirlangimpi (Garden Point) on the northwest coast of Melville Islands and is the most recently formed art centre on the Tiwi Islands. In 1983, Eddie Puruntatameri, Australia’s seminal Aboriginal potter and ceramic artist, set up a community pottery workshop. In 1990 Pirlangimpi Pottery and the Yikikini Women’s Centre were incorporated under the name Munupi Arts and Crafts Association. Munupi Arts and Crafts are highly regarded for the diversity of their works including painting, pottery, carving, weaving, screen prints, etchings, linocut prints, lithographs and screen printed textiles.

Tiwi Design is located in the township of Nguiu overlooking the Apsley Strait. It began in a small room underneath the Catholic Presbytery on Bathurst Island in 1968. Madeline Clear, the art teacher from the local school, worked with Bede Tungatalum and Giovanni Tipungwuti to produce wood block prints. This art form was introduced because of the natural link with traditional wood carving techniques. Today, the Tiwi Design art complex comprises of a carver’s shelter, pottery studio, screen-printing studio, and a painting studio along with an administrative centre and retail gallery. Approximately 100 artists unify under the banner ‘to preserve, promote and enrich Tiwi culture’. Tiwi Design produces a range of fine art ceramic sculptures and functional wares, paintings in ochre, ironwood carvings, screen-printed fabrics, bark and fibre art, bronze sculptures and prints.

Artists: Past and present

| Declan Apuatimi | Jock Puautjimi | |

| Kenny Brown | Fiona Puruntatameri | |

| Theresa Burak | Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri | |

| Glen Farmer Illortaminni | Romolo Tipiloura | |

| Osmand Kantilla | Brenda Tipungwuti | |

| Cyril James Kerinauia | Diane Tipungwuti | |

| Pauletta Kerinauia | John Martin Tipungwuti | |

| Bernadette Mungatopi | Francine Tungatalum | |

| Maria Josette Orsto | Linus Warlapinni | |

| John Pilakui | Jocelyn Black | |

| Darren Puruntatameri | Josephine Burak | |

| Nina Puruntatameri | Brian Farmer Illortaminni | |

| Thelca Puruntatameri | Kitty Kantilla | |

| Vincent (Tiger) Tipiloura | Alan Kerinauia | |

| Conrad Tipungwuti | Margaret Renee Kerinauia | |

| Ita Tipungwuti | Renee Kerinauia | |

| Bede Tungatalum | Janice Murray | |

| Freda Warlapinni | Roslyn Orsto | |

| Margo Wommatakimmi | Mark Puatjimi | |

| Jean Baptiste Apuatimi | Francesca Puruntatameri | |

| Donna Burak | Robert Puruntatameri | |

| Timothy Cook | Therese Ann Tipiloura | |

| Fatima Kantilla | Columbiere Tipungwuti | |

| John Patrick Kelantumama | Giovanni Tipungwuti | |

| Dymphna Kerinauia | Mary Magdelene Tipungwuti | |

| Raelene Kerinauia | Susan Wanji Wanji | |

| Angelo Munkara | Pedro Wonaeamirri | |

| Reppie Orsto |

Further References

Brandl, Margaret, ‘Groote Eylandt, The Tiwi and Wadeye: The Everyday and the Extraordinary’ in Caruana, Wally,(ed.) Windows on the Dreaming: Aboriginal Paintings in the Australian National Gallery, Sydney, 1989

Goodale, Jane, Tiwi Wives: A study of the women of Melville Island, North Australia, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1971

Isaacs, Jennifer, Spirit Country: Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art, Hardie Grant Books, 1999

Kleinert, Sylvia & Neale, Margo (general eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp.716 – 717

Laverty, Colin, Beyond Sacred: Recent paintings from Australia’s Aboriginal communities. The Collection of Colin and Elizabeth Laverty, Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2008

Rey, Una, ‘Kitty Kantilla, From Melville Island’ in Laverty, Colin, Beyond Sacred: Recent paintings from Australia’s Aboriginal communities. The Collection of Colin and Elizabeth Laverty, Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2008, p. 125

West, Margie, ‘It Belongs to No One Else: The Dynamic Art of the Tiwi’ in One Sun One Moon, Aboriginal Art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2007, pp. 125 – 131

Wonaeamirri, Pedro, ‘In Conversation’ in One Sun One Moon, Aboriginal Art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007, pp.132 – 137