Balgo is one of the most isolated of Australia’s desert settlements, located on the northern edge of the Great Sandy Desert and the western edge of the Tanami Desert of Central and Western Australia. Its climatic conditions are harsh, with summer temperatures reaching forty-five degree Celsius and the short winters are cool with night temperatures dropping to five degree Celsius with strong easterly winds blowing from the desert. Balgo is about 830 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs and some 280 kilometres south east of Halls Creek.

Balgo has a fluctuating population due to family, cultural and social responsibilities and obligations, which mean that people often have to travel considerable distances, resulting in a very mobile community. The current population is between 350 and 400, rising to as many as 500 according to season or a major community event.

The community site is part of the 2.6 million hectares of the Balwina Aboriginal Reserve. The Western Desert Aborigines in their movement towards white settlements spread in a fan shaped crescent to Wyndham and Derby to the north; to Strelley in the west; and to Papunya in the East of the Northern Territory. Wirrimanu is the meeting place of the Kukatja tribes from the South, the Walmajarri tribes of the Northwest and the Jaru tribe from the North.

The Kukatja name for the locality of the Balgo township is Wirrimanu, a synonym for Luurnpa, the Warlpiri name for the Red-backed Kingfisher.

Language and Clans

The mission brought together a number of different language groups including Kukatja from the South towards the Gibson Desert, Jaru from the Northern country now the domain of the pastoralist, Walmatjarri from the lands around the Canning Stock Route, Wangkatjungka, and the Pintupi and Warlpiri from the Tanami Desert and the east.

Most of the Balgo community speak Kukatja, which is the main means of everyday communication. While Walmajarri, Jaru, Pintipi, Warlpiri and Kriol are spoken, most of the adults are trilingual.

In 1992, the first full dictionary of the Kukatja language was produced by Father Hilaire Valiquette, which was based on the work compiled by Father Anthony.

History

The Kukatja people’s history of contact with non-Aboriginal people has been associated from the beginning with the Catholic Church. The first impact of the Church was in 1934, when it acquired a cattle station homestead called Rockhole near Halls Creek with the intention of establishing a leprosarium for the Aboriginal people. Hansen’s Disease was reported to be rampant among the Desert Aborigines at that time.

In 1939, Father Alphonse Bleischwitz a member of a German missionary order (The Pallottines) was directed by the Bishop to move further south and took sheep, camels, horses and personnel from the Mission outpost. A suitable site was chosen near the Balgo Hills (Parlku – the grass growing on the slopes of hills – in Kukatja) in 1942. The aim of this settlement was to provide a buffer between the traditional Aboriginal way of life and the new life on the cattle stations where the Aborigines were under the control of the European settlers. Gradually the group was joined by a small group of Aborigines.

Some Aboriginal people from Beagle Bay (the seat of the Catholic Diocese at the time) had come with the priest to act as ‘missionaries’ to the desert Aboriginal people. This group were later joined by some members of the Religious Order of Sisters established by Bishop Raible for the indigenous people of the Kimberley. In 1956 a group of St John of God Sisters joined the Pallottines to further expand the mission community.

In the early 1960s, difficulties arose because of a dispute over the site of the mission within the Billiluna pastoral lease, which added to the now urgent problem of establishing an adequate and permanent water supply. A new site, seventeen kilometres to the east, was chosen in 1964 at what is now known as Balgo. Wirrimanu is the name the Kukatja people use for this present site. In 1965, the new site became operational and a primary school was opened in Wirrimanu and was, until the end of 1983, run by the Western Australian Education Department.

Balgo Mission eventually gave way to the Balgo Community, with the Aboriginal Council in 1979. From 1978, the community gradually gained its independence from the benevolent direction of the Mission Superintendent. As Wirrimanu Community, it became incorporated in 1985.

Art and the Art Centre

Although aware of the success of Papunya Tula, the Balgo residents had been somewhat reticent about paintings for a non-Indigenous audience. A direct stimulus came through the establishment of St John’s Adult Education Centre in 1981, which provided literacy and craft programs. Painting followed, initially in ochres.

As a celebration of Father Peile’s twenty-fifth anniversary as a priest, and at the suggestion of Sister Alice Dempsey, the senior law men ritually blended the traditional ochres with the new acrylic paints available through the Adult Education Centre. The senior men wanted to bring the old and the new into alignment and accordingly, Arthur Tjapanangka and Jimmy Njamme performed a ceremony to transfer the power of those traditional ochres to the new colourful synthetic polymer paints. A large banner created by the men was imbued with a variety of pigments, pale green and pink, with red and yellow ochres combined with white and black. Significantly, blue was used by senior rainmaker Mick Gill Tjakamarra to depict water.

The senior women were to take up painting, and like the men were attracted to colour using green for grass and trees, blue for water and red for fire and lightning. In 1986, the first Balgo exhibition, Art of the Great Sandy Desert, was held by the Art Gallery of Western Australia.

A group of some of the original Papunya Tula members set up an artists’ cooperative called Warlayirti Artists, taking its name from the ancestral Kingfisher of the Kukatja people,  which had led them to their country. In 1988, Michael Rae commenced working as the art advisor and supported the use of the bright primary colours.

which had led them to their country. In 1988, Michael Rae commenced working as the art advisor and supported the use of the bright primary colours.

Since its move to a new building, the art centre has flourished and been self-funding and independent since 2002. The centre facilitates as both an exhibition space and a space for artists studios. Warlayirti Artists paint the Tjukurpa of their ancestral homeland, which stretches across the sand dunes of the Great Sandy Desert. Many paintings feature waterholes, which bring life to this desert country, and reflect the artists’ intimate knowledge of country. Their paintings are revered for their bright colours and gestural brushwork. In late 2000, following the establishment of a glass studio, Warlayirti artists started producing fused glass coolamons.

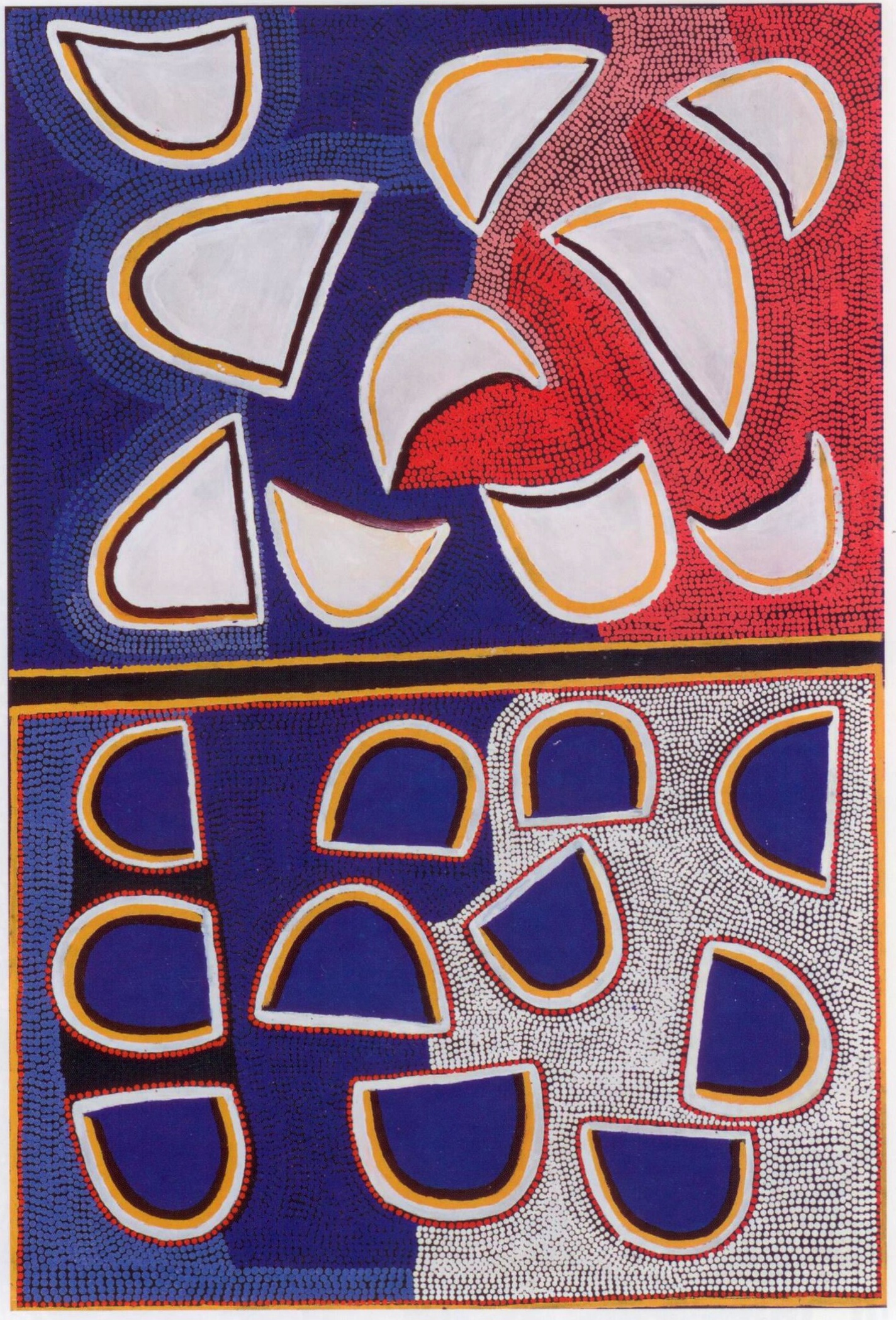

Image: BOXER MILNER 1943–2009, Yakarn, 2003, synthetic polymer paint on linen © the artist’s estate, courtesy of Warlayirti Artists

Significant Creation Stories

According to Marukurru Sunfly – the custodian of the creation story of Luurnpa the Kingfisher – Luurnpa was alone in his country and wanted company to sit down and sing his songs. He set out to find company and travelled north and could find no living being and so flew back to his homeland.

The next day he set out again and this time he saw a snake that emerged from a tiny hole. He flew down and put his beak into the hole to stretch it bigger and saw in it people that looked like stone and he knew that they had been there for a long time under the ground. He breathed into the hole and they all came alive again, but they were not all strong. He sorted them out into two groups, those that were strong enough to be able to follow him and those that were too weak. To the strong ones he said, “Come with me. I need company. I am alone”. He then guided them to his own good country.

He led them from waterhole to waterhole, and they always had water to survive the long hot journey, from the soaks and rock hole. He looked after his people with water and kangaroo, goanna and lots of other bush tuckers along the way. While they were travelling he looked back at his people and said to himself. “Oh, what a mob I’ve got! These people will be my people”. Wirrimanu was the path that the Luurnpa took, and he and his people settled down in Kukatja country and the Luurnpa was happy.1

Artists: Past and Present

| Boxer Milner | Eubena Nampitjin |

| Gracie Green Nangala | Susie Bootja Bootja Napaltjarri |

| Elizabeth Nyumi | Tjumpo Tjapanangka |

| Donkeyman Lee Tjupurrula | Sunfly Tjampitjin |

| Wimmitji Tjapangati | Helicopter Tjungurrayi |

Further References

Caruana, Wally, Aboriginal Art, Thames & Hudson, London, 2003, pp.154-161

Cowan, James, Balgo Hills: Aboriginal Painting. Poster Book, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1994

Glowczewski, Barbara, YAPA: peintres Aborigenes de Balgo et Lajamanu, France, 1991

Isaacs, Jennifer, Spirit Country: Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art, Hardie Grant Books, 1999

Kleinert, Sylvia & Neale, Margo (general eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp.732 – 733

Rae, Michael, Balgo in Crumlin, Rosemary, Aboriginal Art and Sprituality, Harper Collins Publishers, Melbourne, 1991, pp.51-58

Ryan, Judith, with Akerman, Kim, Images of Power: Aboriginal Art Of The Kimberley, National Gallery of Victoria.

Ryan, Judith, Colour Power, National Gallery of Victoria, 2004

Foot Notes

1. See Culture Luurnpa School luurnpa.wa.edu.au ↩