You can read further about Hilda Rix Nicholas on our exhibition page:

You can read further about Hilda Rix Nicholas on our exhibition page:

In the spirit of this year’s NAIDOC week theme, ‘Keep the fire burning – Blak, loud and proud’, we celebrate the painting of Genevieve Kemarr Loy.

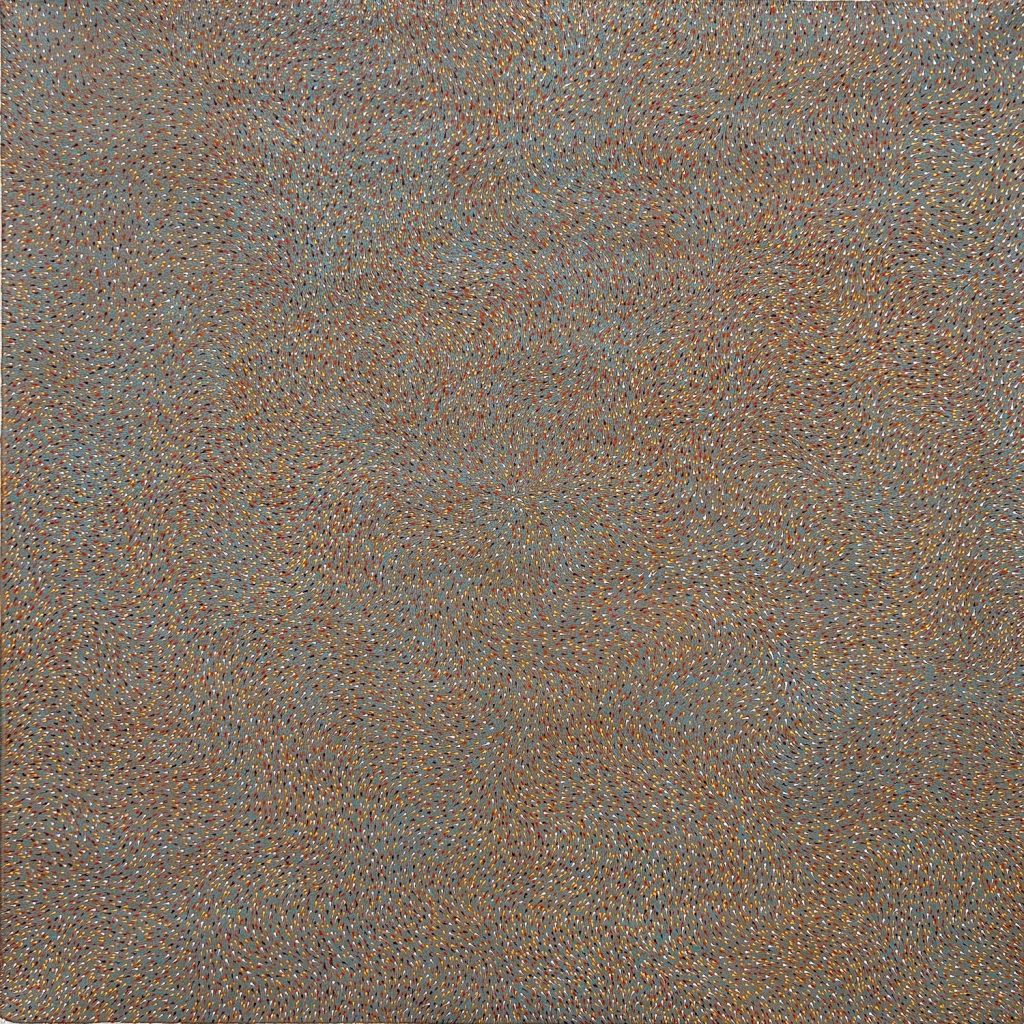

Genevieve Kemarr Loy 1982 – (Anmatyerr) Amperwelkermerr synthetic polymer on linen 92 x 122 cm 223009

Genevieve is a young woman of strength, determination and resilience who continues the family tradition of painting from the Utopia area in remote Central Australia.

Genevieve was driven to start painting at around 12- 14 years old, her curiosity piqued by watching others around her, particularly her dad Cowboy Loy Pwerl and his wives Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray and Carol Kunoth Kngwarray, daughters of Nancy Kunoth Kngwarray. As she grew older, she wanted to learn more about the meanings of the mark making and began to ask questions about the motivation for the paintings. Her father spent much time relaying the stories of homeland to her, especially the bush turkey.

Several years ago, Genevieve moved to Port Augusta to be near her two children, and despite the distance from her country, she continued to paint inspired as always by the flora and fauna of Utopia. Genevieve most often paints the story of Arwengerrp, the Bush Turkey, which has been passed down from her father, himself a collectible artist and important senior elder who sadly died in 2022.

Genevieve has taken on the intricate patterning depicting the tracks the bush turkey makes as it searches for seeds to eat and makes it way to a central waterhole. She infuses the story with her own interpretation, using meticulous dots across the canvas and a harmonious colour palette to create a vibrant, pulsating surface.

Genevieve Kemarr Loy 1982 – (Anmatyerr) Wildflowers 2023 synthetic polymer on linen 200 x 121 cm 223013

Genevieve has more recently made the decision to return to Utopia, continuing to produce beautifully detailed paintings. Just as she learnt from elders in her family, she finds herself now keeping the fire burning, as the inspiration and teacher to a younger generation.

Genevieve has been recognised as a Finalist in a number of art prizes including The Churchie National Emerging Art Award, 2012 (judge’s award winner); Lloyd Rees Memorial Youth Award, 2009; Blake Prize, 2010, 2013; Fisher’s Ghost Art Award, 2010; Hawkesbury Art Prize, 2012; Paddington Art Prize, 2012, 2017; The Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize 2013; Alice Prize 2014, 2016; Grace Cossington Smith Art Award, 2018; Redlands Art Awards, 2018; Ravenswood Australian Women’s Art Prize 2020, 2024.

View selected paintings on our website.

Genevieve Kemarr Loy 1982 – (Anmatyerr) Bush Turkey 2024 synthetic polymer on linen 117 x 75 cm 224017

Although our exhibition centres on John Dent’s paintings, we are excited to be able to show and offer a selection of his etchings, the limited holdings of the artist’s own studio. Dent’s time in Paris allowed him to build on his printmaking skills and techniques at the premier printmaking studio Lacourière Frélaut.

Dent’s etchings are often on a grand scale with intricate and experimental use of line and texture, from a simple lightly scratched line to a rich use of stippling and patterning.

Some of the smaller sized monochrome works have a lovely immediacy, an artist capturing a mood and atmosphere of place.

Dent’s prints reveal his skilled technique, bold use of colour, interest in patterning and the unusual viewpoint of the assembled everyday objects encountered in an interior, all presented with a strong decorative element.

To read further and take A Closer Look At… John Dent’s etchings – please click here.

John Dent: Recent Paintings is now showing throughout July 2024. To preview a selection of works and download the e-catalogue or watch a video of the opening please see our website www.diggins.com.au

For those around Australia with a public holiday on 10 June, we hope you enjoy a long weekend. We look forward to welcoming you to the Gallery from Tuesday 11 to view our current exhibition of paintings by John Dent, showing until the end of June.

With his wide variety of interests, significant mentors and travel experiences, especially time spent in France, Dent has built a successful art career over the past 50 years and is always looking and always learning. Some of his paintings bear a clearer influence of a particular artist or movement, perhaps Baldessin here or Bonnard there, but each work is distinctly Dent.

Preview artworks on our website

Watch the video of the exhibition opening with remarks by Peter Perry OAM, former Director of the Castlemaine Art Gallery and currently working on a publication of John Dent’s art.

The Sydney Fair at The Kensington Room, Randwick Racecourse this weekend Sat 1st and Sun 2nd June. Over 50 dealers showing art, antiques, jewellery, furniture, fashion, collectables and more. We are exhibiting a selection of Australian art from colonial to contemporary paintings, works on paper and ceramics.

See our website for further details.

We are pleased to advise that Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray has been selected as a finalist in this years Hadleys Art Prize, showing at Hadleys Hotel, Hobart 3 – 25 August.

Elizabeth’s painting depicts the leaf, seed and flower of the bush yam, a tuber plant which is an important source of food and medicine. Elizabeth uses thousands of tiny flicks of colour to show the wind moving through the yam plant, producing a beautiful and captivating sense of movement as the coloured marks undulate across the canvas. Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray is from Utopia, N.T. following in the footsteps of the celebrated family tradition of painting.

Congratulations to Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray and Genevieve Kemarr Loy who have both been selected as finalists in this year’s Ravenswood Australian Women Artists’ Art Prize which will be showing at Ravenswood School for Girls, Gordon NSW from 10 – 26 May with their paintings Yam Seeds in My Country (Elizabeth) and Bush Turkey Story (Genevieve). 117 finalists were announced from 1616 entries received for the 2024 Ravenswood Australian Women’s Art Prize.

Elizabeth and Genevieve are both from the Utopia region in Central Australia, building on the legacy of Emily Kam Kngwarray with their intricate paintings depicting the flora and fauna of their country. Elizabeth depicts the seeds, flowers and leaves of the yam, an important source of food and medicine and Genevieve paints the Bush Turkey, which she has inherited from her father. There is a beautiful sense of patterning and movement through their artwork which is imbued with cultural significance.

Genevieve Kemarr Loy 1982 – (Anmatyerr)

Bush Turkey Story 2023 synthetic polymer on linen 120 x 120 cm

Elizabeth Kunoth Kngwarray 1961 – (Anmatyerr)

Yam Seeds in My Country 2023 synthetic polymer on linen 120 x 120 cm

For further information: https://www.ravenswoodartprize.com.au/

Lauraine Diggins Fine Art exhibiting at the Australian Antique and Art Dealers Association Fair at the Malvern Town Hall this weekend 20 – 21 April.

Visit us and view some wonderful artworks including impressive large-scale portraits by Isaac Cohen, Bessie Gibson, Elaine Haxton and Helen Peters; a group of paintings by Hilda Rix Nicholas; a suite of lithographs by Ethleen Palmer; a selection of nudes by Brett Whiteley; a new painting by Michael McWilliams; a lyrical painting by Angelina Ngal; ceramics by Stephen Bowers, Geoff Mitchell and Mark Thompson and much more.

Lauraine Diggins Fine Art extends our warm wishes to all for a happy and safe festive season. We thank everyone who continues to support the Gallery and it has been a privilege to present the exhibition of artworks by Hilda Rix Nicholas. We have enjoyed meeting and speaking with many of you at art fairs in Melbourne and Sydney and look forward to bringing an ongoing selection of Australian art to you in the new year.

The Gallery will close for the extended summer break from Thursday 21 December and reopen Tuesday 30 January 2024. The best contact is via email during this time: ausart@diggins.com.au

Image: Stephen Bowers Camouflage Plate Adelaide Rosella 2023 earthenware with underglaze decoration and clear glaze, diam: 33.5 cm

Our exhibition of paintings and drawings by Hilda Rix Nicholas is now on show after a crowded opening attended by the artist’s granddaughter, Bronwyn Wright and with introductory words by Dr Gerard Vaughan AM, former Director of the National Gallery of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria. A video of this illuminating speech is available to view on our website, where you can also download the illustrated catalogue and read further about the artist with an essay by Dr Sarah Engledow and an insight into the artist’s use of materials in Morocco by conservator, Catherine Nunn.

The exhibition is enhanced by posters, photographs and costumes, giving background and context to the artworks which represent the diverse range of her long and successful career, from Paris to Morocco to Etaples and Brittany, as well as images of Mosman and travels in northern NSW, to her later images from her time at ‘Knockalong’, a sheep station in the Monaro region, including landscapes, portraits and images of her son Rix.

The exhibition is on show until 1 December.

For further details see our website